Now let's see how the government can step in and help provide solutions to externalities. We saw these externalities, right? They are costs or benefits that affect people outside the transaction. We see instances like pollution, vaccinations leading to less contagious populations, among others. Initially, we looked at graphs showing these extra costs or benefits not included in the market, and now we aim to internalize these externalities. This concept relates to incorporating the cost or benefit of the externality into the market transaction, thus making participants account for these additional costs or benefits.

Pertaining to public solutions and private ones, which we'll discuss in other videos, the government has various ways to intervene. One method is through command and control policies where the government sets firm regulations mandating or prohibiting specific actions. For instance, in dealing with positive externalities, the government mandates education because it recognizes the broad societal benefits that may not be accounted for by the market alone. Conversely, in negative externalities, like a factory dumping chemicals into a river, the government enforces regulations prohibiting such actions and may require the installation of filtration systems to handle the chemicals safely.

Moving on, the government also implements market-based policies such as corrective taxes, subsidies, or setting quantity limits. We'll focus primarily on corrective taxes and subsidies in this discussion. Let's delve into corrective taxes, also known as Pigovian taxes, named after the economist Pigou, who won a Nobel Prize for identifying how taxes and subsidies can manage externalities. His principle was to impose taxes or provide subsidies equivalent to the external cost or benefit. With proper quantification, these financial adjustments can bring production to an optimal level that considers societal costs and benefits.

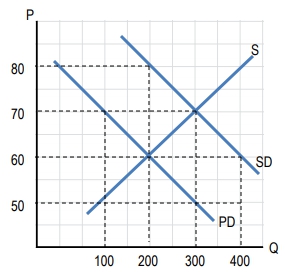

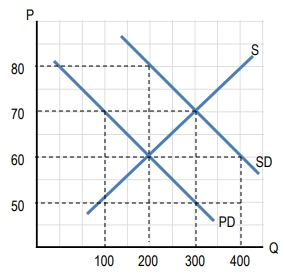

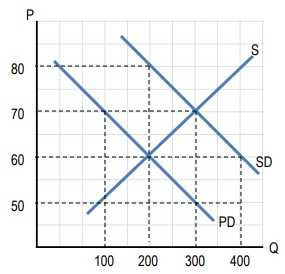

We learned that without such policies, markets might overproduce or underproduce, not considering the full impact on society. For example, considering negative externalities in pollution, the initial supply curve reflects only the private costs. However, including societal costs for pollution, we find a new supply curve indicating the true cost, including environmental impacts. The government can adjust this inequity with a tax equal to the cost of pollution, moving production to a socially optimal quantity.

Similarly, for positive externalities such as education, where the market underestimates societal benefits, a government subsidy can increase production to reflect true societal benefits, achieving a more efficient outcome.

In illustrating these points with graphs, we depict the equilibrium adjustments made through these taxes or subsidies. These economic tools not only correct market failures but also potentially redirect resources toward other beneficial causes, like environmental conservation through tax revenues.

The idea is not to eliminate pollution entirely but to balance it at a level that maximizes societal benefits against the costs. Acknowledging that some pollution might have offsetting advantages helps frame these policies in a practical economic context rather than purely environmental.

To conclude, this approach towards managing externalities via corrective taxes and subsidies shifts focus towards achieving a quantifiable balance that aligns with societal welfare. In our next sessions, we will explore quantity limits and further compare them with fiscal tools, to better understand diverse methods of addressing externalities.