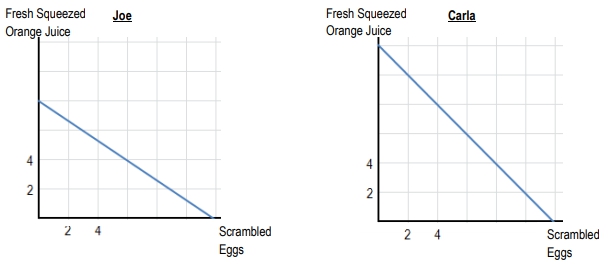

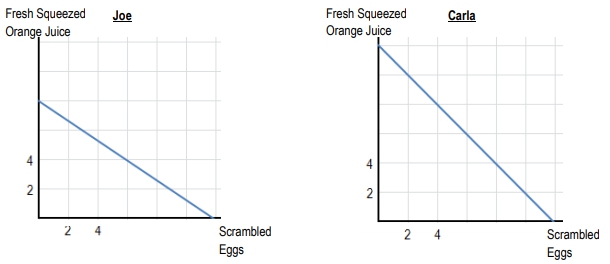

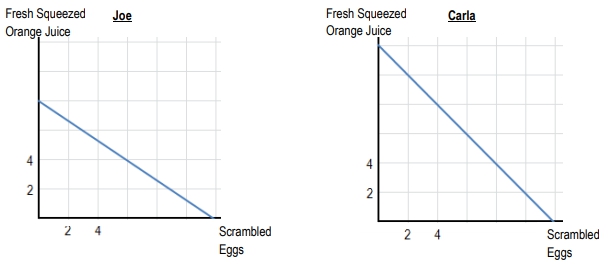

In economics, productivity varies among individuals, firms, and countries, leading to different production capabilities. This concept is illustrated through the production possibilities frontier (PPF), which represents the maximum output of two goods given fixed resources and technology. For instance, consider two students preparing for a party: one can produce 20 gallons of hunch punch or 10 batches of pizza rolls, while the other can produce 30 gallons of hunch punch or 30 batches of pizza rolls. This scenario highlights the differences in productivity and resource allocation.

Specialization plays a crucial role in enhancing productivity. It refers to focusing on the production of goods that one can produce most efficiently. To determine who specializes in what, we assess absolute advantage and comparative advantage. Absolute advantage occurs when one party can produce more of a good with the same resources. In this case, the friend has an absolute advantage in both hunch punch and pizza rolls, producing more of each than the other student.

However, the key to beneficial trade lies in comparative advantage, which is the ability to produce a good at a lower opportunity cost. This means that even if one party is less efficient overall, they may still have a comparative advantage in producing one good over the other. Understanding opportunity cost is essential for determining comparative advantage, as it allows individuals to identify which goods they should specialize in to maximize overall production and benefit from trade.

In summary, by specializing in the production of goods where they hold a comparative advantage, both students can trade and achieve a better outcome than if they attempted to produce both goods independently. This principle underpins the benefits of trade and specialization in economics.