Have you ever been shopping and got a good deal? Well, then you've had a first-hand experience with Consumer Surplus. Let's check it out. So we're going to talk about this idea of willingness to pay, right? This is kind of self-explanatory, right? It's the maximum amount that someone's willing to pay for something, right, the max let me get my red maximum someone's willing to pay, right, that that's kind of what that means. Sometimes you'll hear the word reservation price, that just means the most I'd pay for something, and we've actually already been dealing with this without even knowing it. This is the demand curve is going to represent the willingness to pay of the consumers, right? That kind of makes sense, right? The demand curve shows what prices the consumers are willing to purchase at. So this idea of surplus, right? Of consumer surplus, when we talk about surplus, we're going to be talking about getting good deals, right? Whenever you think of a time you got a good deal, that's the time when these surpluses exist. So when we talk about consumer surplus, right, just like we said is when they're willing to pay more than the market price, right? When you get a good deal, so if you're willing to pay more than the price you actually had to pay, you got some consumer surplus there, and a great example I can think of is Uber, right? Uber now has these insanely cheap well it's 2017 and their rides are still insanely cheap, right? And you know maybe you would expect to pay or be willing to pay somewhere around $20 or $25 for a taxi ride across town or to the airport and now you can get that same taxi ride to the airport for $5, $10 right? It's insane, they've lowered the price of these rides insanely to the point that people are actually using taxis again, right? Think about I never used taxis until Uber came out, and if you don't have Uber, just use my code for your first free ride, get I'm just kidding. Alright. So let's let's go on here. Let's talk about the the formula for consumer surplus which is pretty simple. It's exactly what we've been saying. It's a difference between the willingness to pay of the consumer and the market price, right? So that's going to be the maximum willingness to pay, just to reiterate and the market price, right, and over here I'm going to write Uber so you don't forget this example. Cool. Alright so when we talk about willingness to pay and actually the demand curve, we're going to start talking about this idea of marginal benefit. All right, so remember, we brought this up before and I remember stating that this is going to be a really important topic, marginal benefit, marginal cost, well the idea here is that the demand curve basically represents the marginal benefit to society, to the consumer and to society, of these trades being made, right, of these exchanges. So the idea is maybe you went to, I don't know, to the store and bought a DVD, right? Maybe when you went to the store you loved this movie, you've been looking for this DVD, you would be willing to pay $20 for this DVD, right? And you end up going to the register and it costs $12 right, so your benefit is still this you we could say you had like $20 worth of joy you were going to get out of this movie, right, that's what it represented to you, but you only had to pay $12, right, But that benefit to you was $20 though, right? It wasn't a $12 benefit, it was a $20 benefit even though you paid 12. So we'll think of the demand curve as that marginal benefit. Alright. So let's go ahead and do this simple example in a small market and talk about consumer surplus. Alright so we've got a small market with Cartman, Kyle, Stan, and Kenny, four names I kind of just picked at random, and just to keep things simple in this market, we'll say that each person's only willing to buy one thing. They're only going to buy 1 each. Right? If they could if they're going to buy it, they'll buy 1. They're not going to buy 3 or 4 of the same just to keep it simple, we'll say it's something like that, like they're in the market for like a golden cheesy poof or something like that, right, something that they only need one of and if you don't get it, this is like a South Park thing going on, don't worry about it. So let's talk about the different willingness to pay that we have of each consumer. So you'll see Cartman really wants this Golden Cheesy poof and is willing to pay up to $8 for it. Kyle, $6, Stan, $4 and Kenny, $2. So let's go ahead and put these onto our graph here. Right? We've got our price and our quantity axes there, and we've got some prices there, some quantities. It's all set up for us. So we're going to say at a price of $8 how many people are willing to buy? Well we've got just Cartman, right, so there's going to be one quantity demanded at a price of $8, and what about at a price of $6 well now Cartman and Kyle both buy, right? So we'll be right here. Stan down here. That's at a price of $4 3 people get in and a price of $2. All 4 of them are in the market and 4 will be exchanged there. So it almost looks like we got a demand curve here, right? You're ready to connect these points, but actually we've got kind of a funky demand curve in this case because it's such a small market that there's not people in between these points. So you could imagine like instead of connecting these diagonally like this, there's really nobody in the market at this price of $7 right? It would still only be Cartman buying at that price, So we actually get this funky looking curve. Give me a second. That looks something like this. It's going to have this stair step kind of look. So it's jagged because it's such a small market that we don't get that smooth curve from having a lot of buyers and a lot of, yeah, a lot of buyers in the market. So we get this kind of stair step thing going on here, right, and that makes sense because at a price of $7 if we look right here, it's still only Cartman that buys, right, so we have a quantity of 1 at a price of $7 or $8 right? So that's kind of how we're going to draw it in this small case. It's not so important, but it's going to help us do this example easier. It helps us visualize the surplus. So let's go ahead and start with Cartman or excuse me, start with this price of $7 right? So let's say the price is $7 what is consumer surplus? How much is going to be exchanged here? Well we'll see that only Cartman wants to get in the market, right? So he's willing to pay $8 but he only has to pay 7, right? Minus 7, so he has a consumer surplus of 1 there. How about Kyle? Well, at a price of $7, Kyle's not going to buy, right? His willingness to pay is $6 He doesn't buy at $7, so he doesn't get any surplus if he doesn't buy anything. So he has no surplus. He didn't buy. Stan also has a willingness to pay lower and so does Kenny, right? None of them are going to buy. Only Cartman gets in this market. So at the bottom, I've got this summary. I'm going to get out of the way so we can fill these boxes. We've got a summary of what happened, right? Quantity demanded and consumer surplus. Total consumer surplus in each situation. So at a price of $7, quantity demanded was just the one, right? Cartman's the only one that buys when the price is $7 and total consumer surplus is 1 which is Cartman's consumer surplus. I want to show you that on the graph real quick. So this total consumer surplus of 1, I'm going to mark this green because I'm going to mark the area in green over here. This consumer surplus of 1 is represented by this area right here that I'm marking in green, Right? Just that area above the price of $7. Right? So there was our price of $7 and our consumer surplus is above that line and and below the maximum price there that he was willing to pay. So just so you can see right, 8 minuteus 7, right, that's going to be this length right here is 8 minus 7 which is 1, and this area right here, although it looks like 2 because it but our notice how our graph is 1, 2, 3, 4 like that. So that's 1 as well. So 1 times 1 is 1 and that's our consumer surplus of 1. Okay. So let's go on to a price of $5 What happens at a price of 5 dollars? Well, Cartman's still going to buy it. Right? But now he's getting an even better deal. He's going to be even happier about this. So 8 minus 5, he is going to get 3 consumer surplus instead of 1 now. Right? Notice how his consumer surplus has grown. How about Kyle? Well, at a price of $5 Kyle does get in the market. Right? He's willing to pay $6, but the price is $5. So now Kyle is going to buy, and he'll have a consumer surplus of 1. Right? 6 minuteus the market price of $5 gives us 1. Stan, he still doesn't get in, right, because the price is $5 and he's only willing to pay $4, so he's still not going to buy. He has no consumer surplus. Kenny also will not buy because his willingness to pay is too low. Alright, so what happened in this situation? How much quantity was exchanged? Well now Carmen bought 1 and Kyle bought 1, right? So there was 2 exchanged, And how about the consumer surplus, right? The consumer surplus is now Cartman's 3 plus Kyle's 1 is is 4. Right? So the price went down and consumer surplus increased. That kind of makes sense. Right? Everyone's getting good deals, as the price goes down. The good deals, keep on coming. So I'm going to mark this area on the graph in blue, right, but I wanna I'm going to go piece by piece because I wanna show you, where each surplus is. So remember, this spot right here is Cartman's demand. Right? This this spot, on the graph, the price of 8, he's willing to demand. Right? And this right here represents Kyle, and we could say that this one, just to put them all in here is Stan and that's Kenny, right? So Cartman's consumer surplus is right here, right, and his grew. At a price of 7, he had 1 consumer surplus and now he has 3. So let's see that area right there. So he's adding to his consumer surplus this blue area that I just put in right here, right? That's Cartman's additional consumer surplus at this price of $5 right? This is the price of $5 right here, but now Kyle is also getting some consumer surplus surplus right and that's represented by this area here. Kyle's demand and it's still above that price of $5 right. So that's what we have right there. That additional area is 3 and it represents the additional consumer surplus that gets us to a total consumer surplus of 4 because Cartman already had a little bit. Alright, so let's go on to this last case when the price is $4 right? Right? So now the price has dropped again to $4 Cartman's consumer surplus, what do you think? It's going to keep increasing, right, because he's getting better and better deals So he's getting more and more surplus. 8 minus 4 equals $4. Kyle, $6. His is going to grow as well, right? He was buying before, he's going to keep buying so his consumer surplus grew to 2. How about Stan? Now Stan, he is going to get into the market, right? The price is $4, he's willing to pay $4 4-four, however he still has no surplus, right? He's getting it at the maximum he's willing to pay, and actually in this case, he's actually indifferent whether he buys it or not, because he he's at his maximum willingness to pay, but that doesn't matter. We're going to say that he buys it here. And how about poor Kenny here? Poor old Kenny still is not going to pay. His willingness to pay his $2. The price is 4. He's not going to buy it. Alright. So what's happened in this case? Well now 3 people have bought, right? Cartman, Kyle, and Stan are all in the market. 3 are quantity demanded, and what's our consumer surplus? Well, we've got 4 from Cartman. Kyle's got 2. Stan's got 0. So we got 4 plus 2 plus 0 is 6, right? So let's go ahead and represent this on the graph as well. I'll use this purple this time. Now let's first talk about Cartman's additional surplus. Just like you would expect, it would be this area right here under his previous surplus. Right? So now Cartman's total surplus I'm going to outline in black for just a second just so you see it. Cartman's total surplus is this whole area. Right? All of that all for, excuse me. All of those colors right there all represent a surplus and Kyle's surplus. So he's going to have this additional surplus here, right, so now all that area is consumer surplus and just to reiterate, this would be Kyle's total surplus right here. This area. Right? So his surplus is there and what about Stan? Well Stan did get in the market at $4, but he has no surplus and you'll see that right as there's no space for me to highlight between that price of $4 and Stan's demand right there. Right, so our total consumer surplus is represented by all that highlighted area, the green, the blue and the purple. Alright, so let's go ahead and take this to the full market and see what this looks like once we have a full demand curve. Alright, let's do that in the next video.

- 1. Introduction to Macroeconomics1h 57m

- 2. Introductory Economic Models59m

- 3. Supply and Demand3h 43m

- Introduction to Supply and Demand10m

- The Basics of Demand7m

- Individual Demand and Market Demand6m

- Shifting Demand44m

- The Basics of Supply3m

- Individual Supply and Market Supply6m

- Shifting Supply28m

- Big Daddy Shift Summary8m

- Supply and Demand Together: Equilibrium, Shortage, and Surplus10m

- Supply and Demand Together: One-sided Shifts22m

- Supply and Demand Together: Both Shift34m

- Supply and Demand: Quantitative Analysis40m

- 4. Elasticity2h 26m

- Percentage Change and Price Elasticity of Demand19m

- Elasticity and the Midpoint Method20m

- Price Elasticity of Demand on a Graph11m

- Determinants of Price Elasticity of Demand6m

- Total Revenue Test13m

- Total Revenue Along a Linear Demand Curve14m

- Income Elasticity of Demand23m

- Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand11m

- Price Elasticity of Supply12m

- Price Elasticity of Supply on a Graph3m

- Elasticity Summary9m

- 5. Consumer and Producer Surplus; Price Ceilings and Price Floors3h 40m

- Consumer Surplus and WIllingness to Pay33m

- Producer Surplus and Willingness to Sell26m

- Economic Surplus and Efficiency18m

- Quantitative Analysis of Consumer and Producer Surplus at Equilibrium28m

- Price Ceilings, Price Floors, and Black Markets38m

- Quantitative Analysis of Price Ceilings and Floors: Finding Points20m

- Quantitative Analysis of Price Ceilings and Floors: Finding Areas54m

- 6. Introduction to Taxes1h 25m

- 7. Externalities1h 3m

- 8. The Types of Goods1h 13m

- 9. International Trade1h 16m

- 10. Introducing Economic Concepts49m

- Introducing Concepts - Business Cycle7m

- Introducing Concepts - Nominal GDP and Real GDP12m

- Introducing Concepts - Unemployment and Inflation3m

- Introducing Concepts - Economic Growth6m

- Introducing Concepts - Savings and Investment5m

- Introducing Concepts - Trade Deficit and Surplus6m

- Introducing Concepts - Monetary Policy and Fiscal Policy7m

- 11. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Consumer Price Index (CPI)1h 37m

- Calculating GDP11m

- Detailed Explanation of GDP Components9m

- Value Added Method for Measuring GDP1m

- Nominal GDP and Real GDP22m

- Shortcomings of GDP8m

- Calculating GDP Using the Income Approach10m

- Other Measures of Total Production and Total Income5m

- Consumer Price Index (CPI)13m

- Using CPI to Adjust for Inflation7m

- Problems with the Consumer Price Index (CPI)6m

- 12. Unemployment and Inflation1h 22m

- Labor Force and Unemployment9m

- Types of Unemployment12m

- Labor Unions and Collective Bargaining6m

- Unemployment: Minimum Wage Laws and Efficiency Wages7m

- Unemployment Trends7m

- Nominal Interest, Real Interest, and the Fisher Equation10m

- Nominal Income and Real Income12m

- Who is Affected by Inflation?5m

- Demand-Pull and Cost-Push Inflation6m

- Costs of Inflation: Shoe-leather Costs and Menu Costs4m

- 13. Productivity and Economic Growth1h 17m

- 14. The Financial System1h 37m

- 15. Income and Consumption52m

- 16. Deriving the Aggregate Expenditures Model1h 22m

- 17. Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply Analysis1h 18m

- 18. The Monetary System1h 1m

- The Functions of Money; The Kinds of Money8m

- Defining the Money Supply: M1 and M24m

- Required Reserves and the Deposit Multiplier8m

- Introduction to the Federal Reserve8m

- The Federal Reserve and the Money Supply11m

- History of the US Banking System9m

- The Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 (The Great Recession)10m

- 19. Monetary Policy1h 32m

- 20. Fiscal Policy1h 0m

- 21. Revisiting Inflation, Unemployment, and Policy46m

- 22. Balance of Payments30m

- 23. Exchange Rates1h 16m

- Exchange Rates: Introduction14m

- Exchange Rates: Nominal and Real13m

- Exchange Rates: Equilibrium6m

- Exchange Rates: Shifts in Supply and Demand11m

- Exchange Rates and Net Exports6m

- Exchange Rates: Fixed, Flexible, and Managed Float5m

- Exchange Rates: Purchasing Power Parity7m

- The Gold Standard4m

- The Bretton Woods System6m

- 24. Macroeconomic Schools of Thought40m

- 25. Dynamic AD/AS Model35m

- 26. Special Topics11m

Consumer Surplus and WIllingness to Pay - Online Tutor, Practice Problems & Exam Prep

Created using AI

Created using AIConsumer surplus occurs when a consumer's willingness to pay exceeds the market price, representing the benefit gained from purchasing a good at a lower price. It can be calculated as the difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay and the actual market price. As prices decrease, consumer surplus increases, benefiting both existing and new consumers. The total consumer surplus can be visualized as the area below the demand curve and above the market price, often represented as a triangle, calculated using the formula: .

Consumer Surplus in a Small Setting

Video transcript

Consumer Surplus and Market Demand

Video transcript

Alright. So now let's extend the discussion to the full demand curve here, right. So now you see on the graph that demand curve that we're used to, right, it's not that jagged one anymore. This is that downward demand, the double d's. We've got our price axis and our quantity axis. So how did we get to this kind of full demand curve, right? In this situation, there's more people in the market, right? Before we only had 4 buyers, but now you could imagine, right, Cartman was going to buy for 8, Kyle for 6, whatever, now there's going to be other people. Someone who might be able to be willing to pay $6.25, someone willing to pay $6.50, someone willing to pay $7.30, right? All these different willingness to pay kind of smooth out the line just because there's way more customers now, and now there's the opportunity, we're going to make it, you know, you could buy more than one now too, right. Maybe you would buy the first unit for $6 and another unit for $4, right? You put you could be at multiple places along this line, but, regardless, the idea here is that we've got our smooth demand curve now, right? So our consumer surplus to calculate it, let's say we're at this price here of p. Our consumer surplus is going to be that area just like it says the area below the demand curve and above market price. Right. So here's below the demand curve and above market price. Right. We're going to get this triangle. Right. And that's why we have our triangle formula, right there in the box as well. Right? 12bh. That's how we would calculate this consumer surplus is by taking that area. So we could say that this could be like the base right here right? The base between this point and the market price, and we would have to be given this point right if we were going to calculate it. We don't know what it is. It would have to be given to us or something, and then we've got our height right here right. This is going to be the height of the triangle and what does that represent? Well the height is just the quantity demanded right there at that price right? That's what we see kind of happening here is that that length there is just the quantity demanded. So there you go. If you have those numbers, you'd be able to calculate a Consumer Surplus there.

So now let's talk about the idea of what's going to happen to this Consumer Surplus after a price decrease. So first let's think logically like what do you think? Do you think Consumer Surplus is going to increase or decrease after the price goes down? So if the price goes down, think about it, we're going to have more surplus, right, because people are getting better deals, right? There's the people who were already buying before are going to be getting better deals because the price went down, and now that there's a lower price, new people are going to be getting in the market who are also going to be getting some consumer surplus. Right. So this price decreased just like we saw above. As the price went down and down and down, Cartman's surplus kept rising, the new people's surplus started coming in right, so let's go ahead and see what happens to the surplus here. Let me pop out of the way here. Alright so we're still going to have that same original surplus right? Well first let me mark here we got our price axis, our quantity axis, and now we're at this I'm going to call it PL like low price right? A lower price and let's go ahead and talk about the consumer surplus. So this purple, that's our original surplus, right? The surplus that already existed at the higher price. There was already some surplus at that higher price, we still get that surplus. Well, those consumers that were buying before still get the surplus and then those consumers also get more surplus just like we saw Cartman's surplus increasing as the price dropped. That's going to be represented by this box. So the people who are already in the market are now getting more surplus, because the price went down. They're getting an even better deal. They get more surplus. Alright. So that's represented by that green box is the additional surplus to the people who are already buying, and then this blue box is going to represent new surplus to new customers, right, people who were not in the market before but now that the price decreased, they are in the market, right? So that's going to be our additional surplus is going to be that green and the blue is the extra surplus we just got because of the price decrease, but you can see that the total surplus still makes this triangle, right? We've got, you know, the triangle that includes all of the areas is still our total consumer surplus. All of this area, that is our total consumer surplus so we could still calculate with the 12bh, right, if we had the numbers we needed, we could calculate the area there, but they could also ask us for, you know, these other areas if they wanted to. They could say hey what was the original surplus in this situation, And we would know to calculate the area of the purple. They could say what is the additional surplus to consumers that were already in the market. Right. People who are already buying, what additional surplus did they get? We would know it's this green box here, right. The green area, that whole green area, and I'm drawing the boxes smaller just so you can see, but it does include the whole area there. And then they can also ask us what is the new surplus to new consumers at the new price, right. So we would have to calculate this little area down here, right, and they would have to give us the numbers right. We would have to have numbers for prices at the different points and different quantities right, so we would have to have a bunch of information, but we could calculate those areas, right. So that's about how it is, with

Consumer Surplus

Video transcript

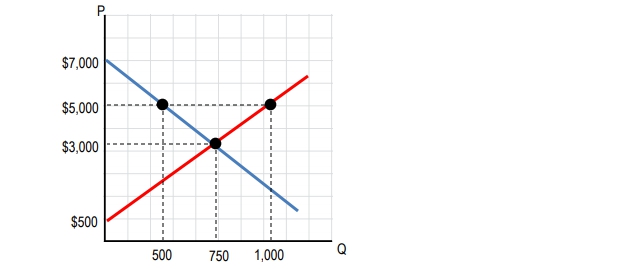

The graph below represents the market for funky fresh rhymes. At a price of $3,000 per funky fresh rhyme, what is the consumer surplus? Alright. Cool. So, what do we have here? They're asking us for consumer surplus, right? We've got a bunch of quantities on the graph, a bunch of prices, we've got our curves there, right? They're asking us about consumer surplus and remember, that's the area below the demand curve and above the market price, right? We're going to get a triangle out of that, and it's going to be this area right here. I'm going to highlight it in green.

So, our market price, what was it? $3,000 and that's right here. So, we want to get the area above the market price but below the demand curve. Right? This is our downward demand. Right? The double d. Downward demand right here. Let's go ahead and highlight that area. So, it's all of this green area right here, right? Below the demand curve, above the market price.

So how do we calculate that? Well, it is a triangle as you can see. Right? So we've got the area of a triangle is going to be half times the base times the height. Right? So, let's go ahead and find out what our base and our height are. So, base and height are going to be these two sides here and this side right here, right? That's going to we'll call that our base. Either one can be base, either one can be height, as long as you pick them.

Alright. So, what's going to be our base, right? Our base is going to be this length between the 3,000 and the 7,000. So, it's going to be half times our base is the difference between the 7,000 and the 3,000, right? It's going to be that 4,000 difference, but I'm going to write it out here. b = 7000 - 3000

What is the length of the height here? What do you see here? We've got a bunch of numbers. Well, it's actually going to be that quantity demanded at that price of 3,000. The quantity demanded is 7.50, and that represents this length, right, from 0 to 7.50 times 750 in that case, right. There's no subtraction needed there because we're going all the way from 0.

So that's pretty much the bulk of it. Let's do this math and figure out what the answer is. C S = 1 2 × 4000 × 750

4000 times 750 equals 3,000,000 and half of that is 1 and a half million, right, and that's going to be the area of that triangle which is our consumer surplus.

So, our answer here at a price of $3,000 per funky fresh rhyme, what is the consumer surplus? It is going to be $1,500,000.

Alright, let's go ahead and move on to the next video.

Use the graph for funky-fresh rhymes above. If price increases from $3,000 to $5,000 per funky-fresh rhyme, what is the change to consumer surplus?

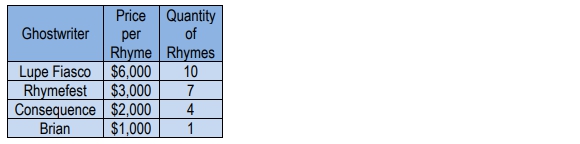

Kanye West is ready to create his next hit single. He knows that he is willing to pay up to $3,000 for a funky fresh rhyme, and that he will need a total of ten funky fresh rhymes to create his hit single. After rounding up his best ghostwriters, he summarized the following schedule. If Kanye values all funky-fresh rhymes equally, what is his maximum consumer surplus?

The demand curve for Nickelback's new album is downward sloping. At a price of $2, nationwide demand is 100 albums. If the price rises to $3, what happens to consumer surplus?

Here’s what students ask on this topic:

What is consumer surplus and how is it calculated?

Consumer surplus is the difference between what consumers are willing to pay for a good or service and what they actually pay. It represents the benefit consumers receive from purchasing at a lower price than their maximum willingness to pay. To calculate consumer surplus, you use the formula:

where b is the base (difference between the highest price consumers are willing to pay and the market price) and h is the height (quantity demanded at the market price). This area forms a triangle under the demand curve and above the market price.

Created using AI

Created using AIHow does a decrease in price affect consumer surplus?

A decrease in price increases consumer surplus. When the price drops, existing consumers who were already purchasing the good benefit from paying less, thus increasing their surplus. Additionally, new consumers who were not willing to buy at the higher price enter the market, adding to the total consumer surplus. This can be visualized as an expansion of the area between the demand curve and the new, lower market price.

Created using AI

Created using AIWhat is the relationship between the demand curve and consumer surplus?

The demand curve represents consumers' willingness to pay for different quantities of a good. Consumer surplus is the area between the demand curve and the market price, up to the quantity demanded. This area shows the total benefit consumers receive from purchasing the good at a price lower than their maximum willingness to pay. As the demand curve shifts or the market price changes, the consumer surplus area adjusts accordingly.

Created using AI

Created using AIWhat is the formula for calculating consumer surplus in a market with a linear demand curve?

In a market with a linear demand curve, consumer surplus can be calculated using the formula for the area of a triangle:

Here, b is the difference between the highest price consumers are willing to pay (intercept of the demand curve) and the market price, and h is the quantity demanded at the market price. This formula helps visualize consumer surplus as the area under the demand curve and above the market price.

Created using AI

Created using AIWhat is the concept of willingness to pay in economics?

Willingness to pay (WTP) is the maximum amount a consumer is willing to spend on a good or service. It reflects the value or utility the consumer expects to gain from the purchase. WTP is crucial in determining consumer surplus, as it helps identify the difference between what consumers are willing to pay and the actual market price. The demand curve in economics represents the WTP of all consumers in the market.

Created using AI

Created using AI