Alright, so we saw how there could be situations where a firm could be losing money in perfect competition. Now let's see when they're going to decide to shut down. Alright. So a firm might shut down due to the current market conditions, right? The market price might be too low for them to make a profit, or their costs might be too high in the current settings, right? There's going to be some reason why they don't want to produce anymore. Okay, and I want to make a quick distinction between a firm shutdown and a firm exit. Okay, when a firm shuts down, okay, so shutting down means they're going to produce no output temporarily, okay? Temporarily, there we go. Temporarily, so it's going to be a short-run shutdown, okay? They shut down in the short run. Right? Remember short run and long run, we're going to dive into that here a little more. So when a firm exits, when we talk about exiting, they're going to produce no output forever, right? They're done in this market. They're like, wait that's not for me anymore, I can't make money there. So that's in the long run that a firm might exit the market entirely, right? So remember when we talked about the short run and the long run? In the short run, there are fixed costs, right? That was the definition of the short run is that there are some costs that we have fixed, and we have to pay them no matter what, right? So when we think about a shutdown decision, when we're going to shut down, we're going to have to pay those fixed costs anyway. So the relevant costs when we think about shutting down are the variable costs, right? Because those fixed costs, whether we produce units or if we don't produce units, those fixed costs are going to be there, right? In the short run, the fixed costs must remain fixed costs, right? They're going to be there no matter what and this brings up the idea of a sunk cost. You might have heard this before. So a sunk cost is a cost that cannot be recovered, okay? So in this case, it could be something like what we're dealing with here, right? Maybe you paid some amount to rent a factory or something, right? You might have paid to rent the factory, and whether you produce units or you don't produce units, you're going to have to you've already paid that amount, right? You're not going to get that money back. You've paid the rent for that factory. It can't be recovered, right? So this idea of sunk cost, it's this idea of like no refunds, right? If you can't get a refund on money you spent, let's say you buy a ticket to a concert, usually Ticketmaster hits you with that non-refundable ticket, right? Once you buy it, you can't send it back, you can't get a refund for it even if the concert hasn't happened yet, right? So there's no refunds, it's a sunk cost or something like a contractual commitment, right? So let's say you signed a lease, right? You signed a lease to rent the apartment you're living in, well, you can't get out of that lease, right? You're stuck in the lease for a year, you're going to have to live there for at least that time, that cost is sunk, right? Even the lease payments you haven't made yet, right? The rent that you're going to pay next month, there's no way out of it, right? You're going to have to pay that cost, you can't recover it. Sunk cost, okay? So now that we've kind of set up the playing field here for the shutdown, let's go ahead in the next video. Let's see an example of a situation where a firm might want to shut down. Alright, let's do that now.

- 0. Basic Principles of Economics1h 5m

- Introduction to Economics3m

- People Are Rational2m

- People Respond to Incentives1m

- Scarcity and Choice2m

- Marginal Analysis9m

- Allocative Efficiency, Productive Efficiency, and Equality7m

- Positive and Normative Analysis7m

- Microeconomics vs. Macroeconomics2m

- Factors of Production5m

- Circular Flow Diagram5m

- Graphing Review10m

- Percentage and Decimal Review4m

- Fractions Review2m

- 1. Reading and Understanding Graphs59m

- 2. Introductory Economic Models1h 10m

- 3. The Market Forces of Supply and Demand2h 26m

- Competitive Markets10m

- The Demand Curve13m

- Shifts in the Demand Curve24m

- Movement Along a Demand Curve5m

- The Supply Curve9m

- Shifts in the Supply Curve22m

- Movement Along a Supply Curve3m

- Market Equilibrium8m

- Using the Supply and Demand Curves to Find Equilibrium3m

- Effects of Surplus3m

- Effects of Shortage2m

- Supply and Demand: Quantitative Analysis40m

- 4. Elasticity2h 16m

- Percentage Change and Price Elasticity of Demand10m

- Elasticity and the Midpoint Method20m

- Price Elasticity of Demand on a Graph11m

- Determinants of Price Elasticity of Demand6m

- Total Revenue Test13m

- Total Revenue Along a Linear Demand Curve14m

- Income Elasticity of Demand23m

- Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand11m

- Price Elasticity of Supply12m

- Price Elasticity of Supply on a Graph3m

- Elasticity Summary9m

- 5. Consumer and Producer Surplus; Price Ceilings and Floors3h 45m

- Consumer Surplus and Willingness to Pay38m

- Producer Surplus and Willingness to Sell26m

- Economic Surplus and Efficiency18m

- Quantitative Analysis of Consumer and Producer Surplus at Equilibrium28m

- Price Ceilings, Price Floors, and Black Markets38m

- Quantitative Analysis of Price Ceilings and Price Floors: Finding Points20m

- Quantitative Analysis of Price Ceilings and Price Floors: Finding Areas54m

- 6. Introduction to Taxes and Subsidies1h 46m

- 7. Externalities1h 12m

- 8. The Types of Goods1h 13m

- 9. International Trade1h 16m

- 10. The Costs of Production2h 35m

- 11. Perfect Competition2h 23m

- Introduction to the Four Market Models2m

- Characteristics of Perfect Competition6m

- Revenue in Perfect Competition14m

- Perfect Competition Profit on the Graph20m

- Short Run Shutdown Decision33m

- Long Run Entry and Exit Decision18m

- Individual Supply Curve in the Short Run and Long Run6m

- Market Supply Curve in the Short Run and Long Run9m

- Long Run Equilibrium12m

- Perfect Competition and Efficiency15m

- Four Market Model Summary: Perfect Competition5m

- 12. Monopoly2h 13m

- Characteristics of Monopoly21m

- Monopoly Revenue12m

- Monopoly Profit on the Graph16m

- Monopoly Efficiency and Deadweight Loss20m

- Price Discrimination22m

- Antitrust Laws and Government Regulation of Monopolies11m

- Mergers and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)17m

- Four Firm Concentration Ratio6m

- Four Market Model Summary: Monopoly4m

- 13. Monopolistic Competition1h 9m

- 14. Oligopoly1h 26m

- 15. Markets for the Factors of Production1h 33m

- The Production Function and Marginal Revenue Product16m

- Demand for Labor in Perfect Competition7m

- Shifts in Labor Demand13m

- Supply of Labor in Perfect Competition7m

- Shifts in Labor Supply5m

- Differences in Wages6m

- Discrimination6m

- Other Factors of Production: Land and Capital5m

- Unions6m

- Monopsony11m

- Bilateral Monopoly5m

- 16. Income Inequality and Poverty35m

- 17. Asymmetric Information, Voting, and Public Choice39m

- 18. Consumer Choice and Behavioral Economics1h 16m

Short Run Shutdown Decision: Study with Video Lessons, Practice Problems & Examples

Created using AI

Created using AIIn perfect competition, firms may decide to shut down temporarily if the market price falls below their average variable cost, leading to economic losses. A firm incurs fixed costs regardless of production, making variable costs crucial in shutdown decisions. For instance, if a farmer's revenue from crops is less than the cost of seeds, they may choose not to produce. The shutdown point is where price equals the minimum average variable cost, indicating that producing would result in greater losses than not producing at all.

We shutdown the business if producing units will cause us to lose more money.

Short Run Shutdown Decision

Video transcript

Short Run Shutdown Decision (continued)

Video transcript

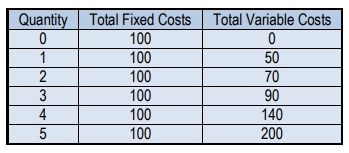

Alright, so let's continue with this example and let's see where we might shut down in the short run. Okay, so we've got a farmer who paid $1,000 to rent a field for the season, and seeds cost $200. Should the farmer produce this season? Alright, we want to see whether they're going to shut down or not. The only thing left is how much money they are going to make from the crop from the seeds, right? So we've got two scenarios here. We've got a revenue of $500 and a revenue of $100.

Notice the first thing we've got here: this $1,000 to rent the field - the farmer already paid it, it's a sunk cost, right? He's not going to be able to get that money back no matter whether he goes ahead and buys the seeds and produces a crop or he just lets the field sit there. Either way, he's out that $1,000.

Let's start here on this left-hand side where we've got revenue of $500. If he chooses to plant the seeds, he's going to get revenue of $500 from the crop. In the first scenario, he doesn't produce anything, right? No production. In that case, he's going to lose the $1,000 he paid for the field and didn't produce anything. Now, let's say he does produce. He's going to spend the $200 on seeds and sell them, right? First, let's think about revenue. He's going to have a total revenue of $500 from the sale of the seeds, but what about his total costs? Well, he's got the $1,000 for the field and the $200 for the seeds; he's got $1,200 in total costs. His profit, or loss in this case (we're going to put losses in parentheses), is going to be his total revenue minus his total costs: $500 minus $1,200. Well, that leaves him with a loss of $700.

So what's the best scenario for him? He can either not produce and lose $1,000 or he can produce and only lose $700. It's still a lose-lose situation for him; there's no way for him to make a profit, but at least he can lose less money. So in this scenario, the best option is to produce and have a loss of $700.

Now look at the other side, the revenue from sales is only $100. If he doesn't produce, he's only going to have a loss of $1,000. If he decides to produce, he's going to have total revenue of $100. Again, he's got the $1,000 for the field and $200 for the seeds. His total costs are $1,200, so his profit is going to be $100 in revenue minus $1,200 in costs, resulting in a loss of $1,100. Producing this time results in a greater loss; hence it makes sense for him to not produce and just face a $1,000 loss instead of $1,100.

In one case, the price was above the variable cost. The variable cost was the seeds. If we continue production, we need to spend money on seeds. So those variable costs are what's important here. The shutdown condition is if the price falls below the minimum of the average variable cost curve.

So, we're bringing another curve into the mix here. We have dealt with the marginal revenue and the marginal cost to find the profit-maximizing quantity. We confronted the average total cost curve when using the price and the average total cost to calculate our profit or our loss, and now we're using the average variable cost curve to find out where we're going to shut down. If the price is below that variable cost curve, then we're going to shut down.

The shutdown point, that minimum point on the average variable cost, is the shutdown point. In this first box, the total revenues are less than the variable costs, so we shut down, as seen in the second example where the revenues were $100 and the variable costs were $200. You shut down if the total revenue is less than the variable cost.

Let's do a little algebra to rearrange this. Divide both sides by q. We then have total revenue divided by q is less than variable cost divided by q. What happens when we divide by q? We're talking about the average, taking the average revenue and average variable cost. If you recall, average revenue is just the price. The left-hand side of this equation is the price, and the right-hand side is the average variable cost. If the price is less than the average variable cost, then we will shut down.

We'll pause here and continue in the next video, where we're going to see all this information on a graph and determine where we are going to shut down. Let's do that now.

Short Run Shutdown Decision on the Graph

Video transcript

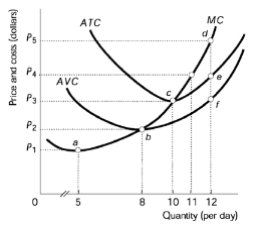

Alright, cool. Now let's check out this graph where we've got our marginal cost curve, we've got an average total cost curve, and then now we've added the average variable cost curve, right? So now we're talking about average variable cost as well when we're talking about shutdown. And I want to make a quick point here, this bullet. We're only going to talk about average variable cost, in this section and in perfect competition, average variable cost, the only time it comes up is in the short run shutdown decisions. Okay? So this is the only time you have to think about average variable cost is when we're dealing with short run shutdown. Okay? Other than that, average variable cost isn't going to come up. So that should help you kind of zone in when we're going to use this. Okay? So I've got these cost curves on the graph. Let's go ahead and set some different prices, right? If we put a high price, a low price, let's see what happens, okay?

So first price I'm going to set here. I'm going to put a price up here. I'm going to call it the high price. Price high, right? And at that high price, remember in perfect competition that price is our marginal revenue, always our average revenue, right? But that marginal revenue because we want to see where the marginal revenue and marginal cost curve cross, right? That's where we're going to produce. So let's go ahead and draw in our demand curve right there, right? We've got the horizontal demand for a firm in perfect competition. So at this high price, what's going on here? We're going to have this marginal cost and marginal revenue, right? The price is our marginal revenue curve crossing right there. That is going to be the quantity we want to produce and now what's going on in this case? There are two things we want to know. First, are we going to shut down? So in this case, notice that our price is above our average variable cost, right? And that's what we see over here. Price and average variable cost, what's the relationship? Well, if the price is less than the average variable cost, we would shut down, but that's not what we see here, right? The price is higher. We're able to cover those variable costs, so we are going to produce in this case. So the first question, are we going to produce? Yes. The second question, are we going to make a profit? Right? So we know we're going to produce right there and when we want to check if we're going to make a profit, we got to see if we're covering our average total cost. So that goes to this curve right here and we see that the price is greater than the average total cost, so the money we're bringing in is more than the money we're spending, we are making a profit there, right? So at that high price, we do make a profit and we do produce, alright?

So now let's try some sort of medium price here. Okay. I'm going to erase this stuff. Whoops, I'll leave the price in there. Okay. And I'll erase this stuff so that we can do another example here. Alright. Let's go ahead and pick a medium price. So I'm going to pick something around here. Price medium and again this is also our marginal revenue in this case, right? So we've got our flat demand curve, supposed to be flat, mine's a little not so flat, but take it as flat and we're going to say that this is where we would produce, right? This is going to be that profit maximizing quantity or loss minimizing quantity, right? So what about in this case? What's going on? First, we want to discuss should we produce? And we produce, right? If we can cover our variable costs and that's what's happening here, right? The price is greater than the average variable cost here, so we should produce, right? We should produce but notice our average total cost. We're not making a profit though, right? Notice in this case, we've got our price right there, but our average total cost is above, right? Our average total costs are higher than our price. So that means that we have a loss in this case, right? We're going to have a loss, but we are going to produce, right? So this is the key point here is that we still produce, but we're losing money, right. So we're above that average variable cost curve but below the average total cost.

Alright, last one I want to talk about right here. Let's pick this real low price down here. Price low, right. So something way down there and remember that is our marginal revenue curve again. So here, this actually brings up a kind of an interesting point, right? We're crossing our marginal cost curve twice, right? And whenever this happens, you want to pick the point where the marginal cost is increasing, okay? You never pick this point right here where the marginal cost is still decreasing over here, that's not where we want to pick because we're still lowering our cost if we produce more, so there are still benefits to producing more and more, so the point where we actually want to produce would be here if we produce, right? This would be the point where we would want to produce if we're producing. Okay? So now let's think about shall we produce? Well what's happening in this case? The price is less than the average variable cost, right? It's below the average variable cost curve right here. This being average variable cost at that quantity. Well, we're not going to produce, right? And are we going to make a profit or loss? We're going to lose money equal to our fixed cost, right? Our fixed cost since we're not producing, we still have our fixed cost to cover and that is going to be our loss, alright? So in this case, we don't produce when we are below that average variable cost curve and I just want to make one more I guess quick note right here. I'm going to erase this. If we had a price right here, that is our shutdown point right there, right? The minimum of the AVC. Okay, so let me just erase that and go back. I just wanted to point out that shutdown point, alright, but let's leave it like that. Alright, cool. Let's go ahead and move on. Well before we move on, I just want to note that all this information is summarized right here, everything we went over, right? So should we produce? These are kind of the questions we've been asking so far. Should we produce? Well that has to do with average variable cost and then if we are producing, where do we produce? Well it's always going to be at that marginal revenue equals marginal cost, right? And then the last thing, are we making profit? Well that's when we look at our average total cost, right? If we're covering our average total cost, we make a profit. If not, we have a loss. Alright, let's go ahead and move on to the next video now.

The price for a pair of edible underpants is $50. In the short-run, the firm should:

The price for a pair of edible underpants is $50. In the short-run, the firm's total revenue is:

The price for a pair of edible underpants is $50. In the short-run, the firm's profit (or loss) is:

The firm shuts down at any price below:

What is the least amount of output, assuming the firm does not shut down?

If the price falls from P4 to P3, then output will decrease by

Here’s what students ask on this topic:

What is the short run shutdown point in perfect competition?

The short run shutdown point in perfect competition occurs when the market price falls below the minimum average variable cost (AVC). At this point, the firm cannot cover its variable costs, making it more economical to cease production temporarily. Mathematically, this is represented as P < AVCmin, where P is the market price and AVCmin is the minimum average variable cost. If the price is below this threshold, the firm will incur greater losses by continuing to produce than by shutting down and only covering fixed costs.

Created using AI

Created using AIHow do fixed and variable costs affect a firm's shutdown decision?

In the short run, a firm's shutdown decision is primarily influenced by its variable costs, as fixed costs must be paid regardless of production. If the market price is below the average variable cost (AVC), the firm cannot cover its variable costs, leading to a shutdown. Fixed costs, such as rent or equipment leases, are considered sunk costs and do not impact the shutdown decision. The key criterion is whether the revenue from production can cover the variable costs. If not, the firm will minimize losses by shutting down temporarily.

Created using AI

Created using AIWhat is the difference between a firm shutting down and exiting the market?

Shutting down and exiting the market are two distinct concepts. A shutdown is a temporary cessation of production, typically in the short run, due to unfavorable market conditions where the price is below the average variable cost (AVC). The firm still incurs fixed costs during this period. Exiting the market, on the other hand, is a permanent decision where the firm ceases operations entirely, usually in the long run, when it determines that it cannot achieve profitability in the market. Upon exit, the firm no longer incurs any costs associated with production.

Created using AI

Created using AIHow do you determine if a firm should shut down in the short run?

To determine if a firm should shut down in the short run, compare the market price (P) to the average variable cost (AVC). If P < AVC, the firm should shut down because it cannot cover its variable costs, leading to greater losses if it continues production. This is known as the shutdown point. If P > AVC, the firm should continue producing, even if it incurs a loss, as it can cover its variable costs and contribute to fixed costs. The decision hinges on whether the revenue from production exceeds the variable costs.

Created using AI

Created using AIWhat role do sunk costs play in the shutdown decision?

Sunk costs are costs that have already been incurred and cannot be recovered, such as rent or equipment leases. In the shutdown decision, sunk costs are irrelevant because they must be paid regardless of whether the firm produces or not. The focus is on variable costs, which vary with production levels. If the market price is below the average variable cost (AVC), the firm should shut down to avoid incurring additional losses. Sunk costs do not influence this decision, as they are considered fixed and unavoidable in the short run.

Created using AI

Created using AI