In this video, let's discuss what the demand curve for a public good would be and how we come up with the optimum quantity of a public good. First, before we get to public goods, I want to remind you how we create the demand curve for a private good, right. I'm going to go a little quickly on this section because we've had a video that really goes into detail about this and if you guys are still tripped up, after this little discussion, I would suggest just going to the search bar and looking up a video; I'm almost certain it's just called "individual versus market demand", right. So if you just type that in the search bar, you can get that video with a little more detail about these private goods, right, and how we come up with the demand curve for a private good. So let's start here. To create the demand curve for a private good, we're going to add all the individual quantity demanded at each price. Alright. So, at each price, we're going to take the quantity demanded of each person and add it together to get to our market demand. Cheeseburgers, right? Cheeseburgers were one of our good examples of a private good, right? Something that's rival and excludable. So let's go ahead and see what we've got on these 2 pieces so we'll keep it simple, we've got 2 people in this society, 2 individual demands and then we'll find our market demand based on that. But you could imagine this could extend to thousands of people as well. So what we'll see is that this first person at a price of $5, right, we see this price of $5, they're willing to buy 1 cheeseburger, right? One cheeseburger a week at 5 dollars and the second person here on the second graph, right, this is 2 individual demands and market demand on the right, so the second person at that same price of $5 is also willing to purchase 1 cheeseburger, right? So what about at this price of $3? If we see the price go down to $3, then person 1 here is going to buy 5 cheeseburgers that week, right? And person 2 at this lower price will buy 3 cheeseburgers. So let me go ahead and get out of the way here and let's look at the market demand. How do we get to our market demand, from these individual demands? Well, we're going to add all the quantity demanded at each price. So, in the blue circles, right, we have the price of $5 and at that price of $5, we've got one quantity demanded and one quantity demanded, right? There's going to be 2 total quantity demanded and that's what we see here, right? At that price of $5, right, all the way across there, we see 2 are demanded, right, 1 from each person. Now what about at a price of $3? We're going to see that person 1 here is going to demand 5 and person 2 will demand 3, right? So we're going to have 8 total demand on our market demand curve, right? So what did we see happening there? In this case, right, what we were doing is we were adding the quantities demanded. So what we call this is that we were adding, let me do it in red. Add horizontally is what I'm going to say, right, because we're adding the quantities demanded in this case, we're adding horizontally. The quantity plus the quantity gets us this way, right? So that's how we do private goods and remember if this was too quick for you, go back to that other video and get a little more detail on how this happens. Alright, so let's go ahead and let's talk about public goods, right. I'm going to stop the video just so that we can kind of restart fresh and let's pause here and continue in the next video with the demand curve for public goods. Cool, let's do that now.

- 1. Introduction to Macroeconomics1h 57m

- 2. Introductory Economic Models59m

- 3. Supply and Demand3h 43m

- Introduction to Supply and Demand10m

- The Basics of Demand7m

- Individual Demand and Market Demand6m

- Shifting Demand44m

- The Basics of Supply3m

- Individual Supply and Market Supply6m

- Shifting Supply28m

- Big Daddy Shift Summary8m

- Supply and Demand Together: Equilibrium, Shortage, and Surplus10m

- Supply and Demand Together: One-sided Shifts22m

- Supply and Demand Together: Both Shift34m

- Supply and Demand: Quantitative Analysis40m

- 4. Elasticity2h 26m

- Percentage Change and Price Elasticity of Demand19m

- Elasticity and the Midpoint Method20m

- Price Elasticity of Demand on a Graph11m

- Determinants of Price Elasticity of Demand6m

- Total Revenue Test13m

- Total Revenue Along a Linear Demand Curve14m

- Income Elasticity of Demand23m

- Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand11m

- Price Elasticity of Supply12m

- Price Elasticity of Supply on a Graph3m

- Elasticity Summary9m

- 5. Consumer and Producer Surplus; Price Ceilings and Price Floors3h 40m

- Consumer Surplus and WIllingness to Pay33m

- Producer Surplus and Willingness to Sell26m

- Economic Surplus and Efficiency18m

- Quantitative Analysis of Consumer and Producer Surplus at Equilibrium28m

- Price Ceilings, Price Floors, and Black Markets38m

- Quantitative Analysis of Price Ceilings and Floors: Finding Points20m

- Quantitative Analysis of Price Ceilings and Floors: Finding Areas54m

- 6. Introduction to Taxes1h 25m

- 7. Externalities1h 3m

- 8. The Types of Goods1h 13m

- 9. International Trade1h 16m

- 10. Introducing Economic Concepts49m

- Introducing Concepts - Business Cycle7m

- Introducing Concepts - Nominal GDP and Real GDP12m

- Introducing Concepts - Unemployment and Inflation3m

- Introducing Concepts - Economic Growth6m

- Introducing Concepts - Savings and Investment5m

- Introducing Concepts - Trade Deficit and Surplus6m

- Introducing Concepts - Monetary Policy and Fiscal Policy7m

- 11. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Consumer Price Index (CPI)1h 37m

- Calculating GDP11m

- Detailed Explanation of GDP Components9m

- Value Added Method for Measuring GDP1m

- Nominal GDP and Real GDP22m

- Shortcomings of GDP8m

- Calculating GDP Using the Income Approach10m

- Other Measures of Total Production and Total Income5m

- Consumer Price Index (CPI)13m

- Using CPI to Adjust for Inflation7m

- Problems with the Consumer Price Index (CPI)6m

- 12. Unemployment and Inflation1h 22m

- Labor Force and Unemployment9m

- Types of Unemployment12m

- Labor Unions and Collective Bargaining6m

- Unemployment: Minimum Wage Laws and Efficiency Wages7m

- Unemployment Trends7m

- Nominal Interest, Real Interest, and the Fisher Equation10m

- Nominal Income and Real Income12m

- Who is Affected by Inflation?5m

- Demand-Pull and Cost-Push Inflation6m

- Costs of Inflation: Shoe-leather Costs and Menu Costs4m

- 13. Productivity and Economic Growth1h 17m

- 14. The Financial System1h 37m

- 15. Income and Consumption52m

- 16. Deriving the Aggregate Expenditures Model1h 22m

- 17. Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply Analysis1h 18m

- 18. The Monetary System1h 1m

- The Functions of Money; The Kinds of Money8m

- Defining the Money Supply: M1 and M24m

- Required Reserves and the Deposit Multiplier8m

- Introduction to the Federal Reserve8m

- The Federal Reserve and the Money Supply11m

- History of the US Banking System9m

- The Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 (The Great Recession)10m

- 19. Monetary Policy1h 32m

- 20. Fiscal Policy1h 0m

- 21. Revisiting Inflation, Unemployment, and Policy46m

- 22. Balance of Payments30m

- 23. Exchange Rates1h 16m

- Exchange Rates: Introduction14m

- Exchange Rates: Nominal and Real13m

- Exchange Rates: Equilibrium6m

- Exchange Rates: Shifts in Supply and Demand11m

- Exchange Rates and Net Exports6m

- Exchange Rates: Fixed, Flexible, and Managed Float5m

- Exchange Rates: Purchasing Power Parity7m

- The Gold Standard4m

- The Bretton Woods System6m

- 24. Macroeconomic Schools of Thought40m

- 25. Dynamic AD/AS Model35m

- 26. Special Topics11m

Public Goods: Demand Curve and Optimal Quantity: Study with Video Lessons, Practice Problems & Examples

Created using AI

Created using AIThe demand curve for public goods differs from that of private goods. For public goods, which are non-rival and non-excludable, we add individual prices at each quantity demanded to determine the market demand. The optimal quantity occurs where marginal social benefit equals marginal social cost, represented by the intersection of the marginal social benefit curve and the supply curve. This approach ensures that the total value society places on the public good is maximized, highlighting the importance of understanding demand dynamics in public economics.

Demand Curve of a Private Good

Video transcript

Demand Curve of a Public Good

Video transcript

Alright, so here we are, the demand curve of public goods. Before, we were adding quantities at each price; here we're going to do the opposite. We're going to add individual prices at each quantity, okay. So at each quantity demanded, we're going to add the price each person is willing to pay, right. Because remember with public goods, what do we see with public goods? Public goods are non-rival and non-excludable, right. In this case, that same quantity, right, if we were to provide one quantity of a public good, everyone can use that same quantity. In that sense, what we want to do is find how much each person would pay for that quantity of good, and we can add all those prices together, right? If I would pay 5, and you would pay 3, and he would pay 2, and so on, we would add all of those together to find the total amount that society values this public good, right? At that quantity. Let's go ahead and do this in a small setting, right. This isn't going to be a setting with a government. It keeps our example a little easier. We're going to have 2 individuals in this society, right? We're going to have this idea where we've got maybe Jane who owns a restaurant, Jane's Restaurant, and we've got down here Bob, you know, Bob's got his auto shop right, and let's say that Jane and Bob have their restaurant and their auto shop right next to each other, right, and they are the only 2 businesses on this rural road, right. So they are the only 2 businesses that are right next to each other, and they're both scared at night. They think that if while they're not there, their businesses could get burglarized, right? So they are both considering hiring a security guard, and what they notice is that the security guard cannot guard one place without guarding the other, right? This shows that it's non-excludable, right? They can't prevent the guard from if Jane hires a security guard, his presence there is going to also protect Bob's Auto Shop, right? So it's non-excludable in this case, right? They're both going to get the benefit from the security guard being there, right? In the sense right next to each other or whatever. The guard has to protect both businesses at the same time. And it's also non-rival, right? By one business being protected, it doesn't stop the other business from being protected. The same quantity of protection is used by both businesses. Cool.

Let's look at both of their demand curves for this Security Guard. Starting with Jane. If we were going to have 10 hours of security, Jane is willing to pay up to $8 an hour for these 10 hours of security, right. Now, let's look at Bob's graph, I know it doesn't all fit here, but Bob's graph shows that at those same 10 hours, Bob is willing to pay up to $10 an hour, right? And that might be Bob's business, right? He's more worried about his autos than Jane is worried about her restaurant. Whatever it is, they each have their own individual demand for the security service. And just the same, if there were 15 hours of service, now there's more service, they're not getting as much benefit from those later hours of service, it's those first few hours that are most beneficial to them, so you could imagine that they're going to have less demand for a greater amount of hours. So Jane is only willing to pay up to $4 an hour for 15 hours of protection, where Bob would be willing to pay up to $5 an hour for 15 hours of protection here, right. Again, what we're going to see is we have these different prices at these different quantities, but in this case, since it's a public good, right, we can find the total benefit that they would get from having this public good available and that's what the market demand is going to look like. The market demand is going to include their total benefits by adding the price at each quantity, right? So at a quantity of 10 hours, Jane is willing to pay 8 an hour and Bob is willing to pay 10 an hour, right? So we see up above, we were adding vertically, right. We added the curves, the individual demands horizontally, right? We were adding the quantities in that case. In this case, we're going to be adding them vertically, right? We add the prices together. Cool. So that is how we're going to build the demand curve for public goods.

So what is the right amount? What is going to be the optimal quantity of this public good? Well, like we're used to, it's going to be where the marginal benefit equals the marginal cost, right? MB=MC. We've been talking about this throughout the course, right? And here it comes up again. So here we have that marginal benefit curve, and I guess I'm going to put in MSB=MSC as we're talking about society as a whole here, right? This Security Guard is for everyone in the society. Now, what about the marginal social cost? Well, the marginal social cost is just going to be our supply curve, right? If we don't have any externalities in this market, right, the supply of security guards is just going to be the supply curve for security, right, so we found a point where marginal social benefit equals marginal social cost, and that's going to be at a price of $9 for 15 hours of security guard services, right? So that's how we find the optimal quantity, the curves have to be given to you there, at least the cost curve, right? The social benefit curve could be given a bunch of individuals and added up to make the demand, the market demand there. So just to reiterate, the marginal social benefit curve is the sum of the individual values that consumers place on the public good. These values, that's the prices, right? This is the prices that they would be willing to pay for those goods, right? And the marginal social cost curve, well that is just going to be equal to our supply curve, right? As long as we don't have any externalities in this where we'd have to account for those if they did exist, right, we would want to account for all costs even to society, but without dealing with externalities, we're just going to have the marginal social cost be equal to the supply curve, right? We're going to find that point where marginal social benefit equals marginal social cost, and that's going to be the quantity, the optimal quantity of this good. Cool. So that's how we build the demand curve and find the optimal quantity of public goods. Let's go ahead and move on to the next video.

The benefit of an additional unit of a public good is:

If the benefit of a public good does not exceed its cost:

To find the benefit of an additional unit of a public good, we sum the individual demand curves:

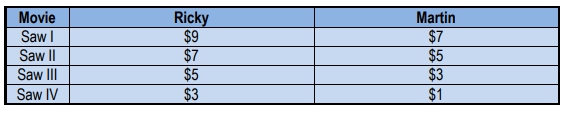

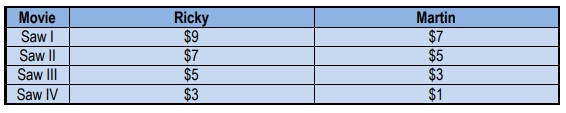

Two roommates plan to spend their evening with a marathon of Saw horror movies. Because it is a marathon, they must start with the first movie in the series and continue in order. Their willingness to pay for the rental of each movie is as follows:The marginal benefit from renting the third movie is:

Two roommates plan to spend their evening with a marathon of Saw horror movies. Because it is a marathon, they must start with the first movie in the series and continue in order. Their willingness to pay for the rental of each movie is as follows:If each movie rental costs $6, how many movies should they rent?

Which of the following is not a possible solution to the tragedy of the commons?

Here’s what students ask on this topic:

What is the difference between the demand curve for public goods and private goods?

The demand curve for public goods differs from that of private goods primarily in how it is constructed. For private goods, which are rival and excludable, the market demand curve is derived by horizontally summing the individual quantities demanded at each price. In contrast, for public goods, which are non-rival and non-excludable, the market demand curve is derived by vertically summing the individual prices each person is willing to pay for each quantity. This means adding the prices at each quantity to determine the total value society places on the public good.

Created using AI

Created using AIHow do you determine the optimal quantity of a public good?

The optimal quantity of a public good is determined where the marginal social benefit (MSB) equals the marginal social cost (MSC). The MSB curve is the sum of the individual values consumers place on the public good, while the MSC curve is typically the supply curve, assuming no externalities. The intersection of these two curves indicates the quantity at which the total value to society is maximized, ensuring efficient allocation of resources.

Created using AI

Created using AIWhy do we add prices vertically for public goods?

We add prices vertically for public goods because they are non-rival and non-excludable. This means that the same quantity of the good can be consumed by multiple individuals simultaneously without reducing its availability to others. Therefore, to determine the total value society places on each quantity of the public good, we sum the individual prices each person is willing to pay for that quantity. This vertical summation reflects the collective willingness to pay for the public good at each quantity level.

Created using AI

Created using AIWhat is the marginal social benefit (MSB) in the context of public goods?

The marginal social benefit (MSB) in the context of public goods is the total benefit that society receives from consuming an additional unit of the public good. It is calculated by summing the individual values that all consumers place on that additional unit. The MSB curve represents the collective willingness to pay for each quantity of the public good, reflecting the aggregated benefits to society.

Created using AI

Created using AIHow is the supply curve related to the marginal social cost (MSC) for public goods?

The supply curve for public goods is typically equated to the marginal social cost (MSC) curve, assuming no externalities. The MSC represents the cost to society of providing an additional unit of the public good. In the absence of externalities, the MSC is simply the supply curve, indicating the cost of producing and supplying the public good. The optimal quantity of the public good is found where the MSC intersects with the marginal social benefit (MSB) curve.

Created using AI

Created using AI