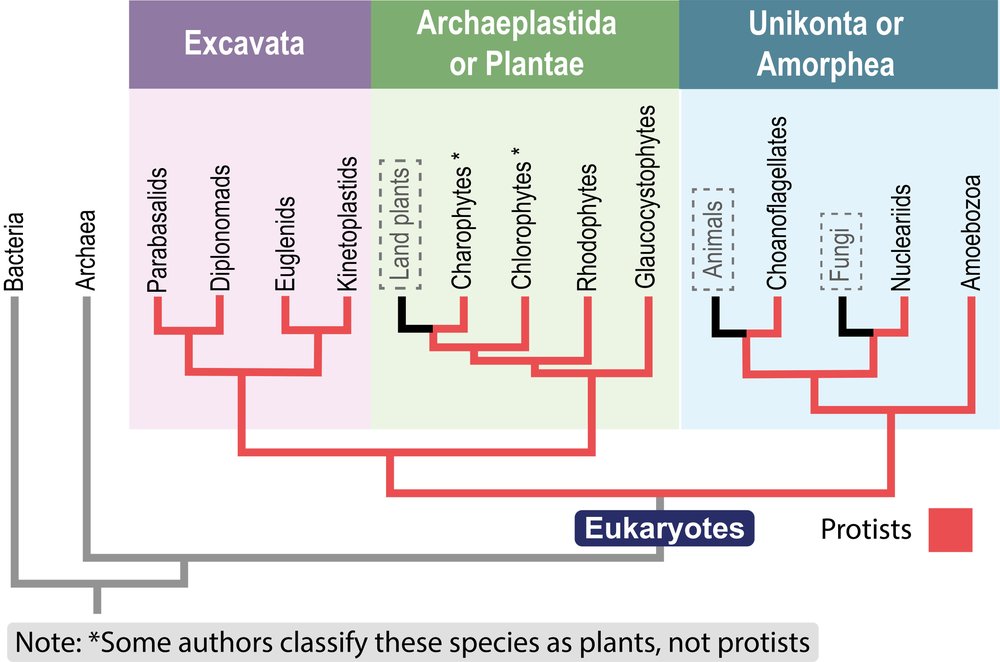

Protists exhibit remarkable diversity, making their classification and evolutionary relationships complex. Current research suggests that all eukaryotes, including protists, can be organized into four primary supergroups: Excavata, SAR, Archaeplastida, and Unikonta. These supergroups are established based on genetic and morphological studies, with a strong emphasis on genetic data.

The SAR supergroup is an acronym representing three distinct lineages: stramenopiles, alveolates, and rhizarians. The Archaeplastida group is sometimes referred to as Plantae in various texts, as it encompasses land plants. Notably, the charophytes and chlorophytes are often debated; some classifications consider them plants rather than protists, highlighting the ongoing discussions in protist taxonomy.

Unikonta includes both animals and fungi, with the term "Unikonta" gradually being replaced by "Amorphea" in scientific literature. However, this change is not universally adopted, and it is unlikely to be a focus in academic assessments.

As we delve deeper into each supergroup in subsequent discussions, understanding these foundational concepts will be crucial for grasping the complexities of protist diversity and their evolutionary significance.