41. Immune System

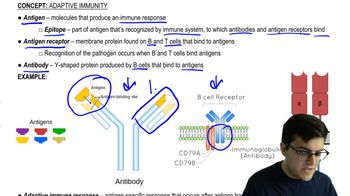

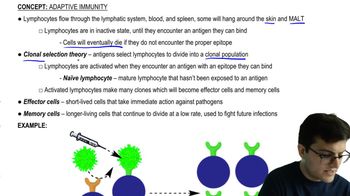

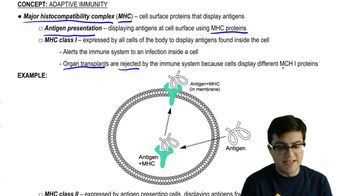

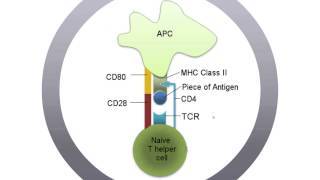

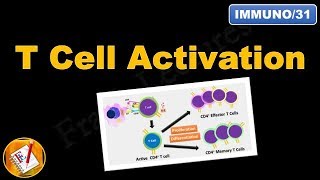

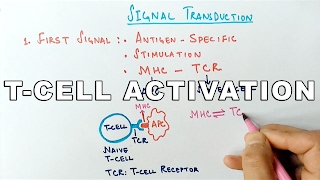

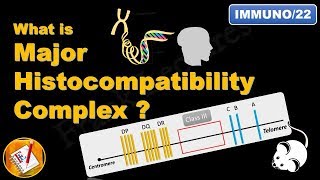

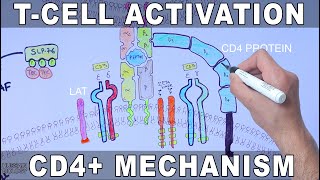

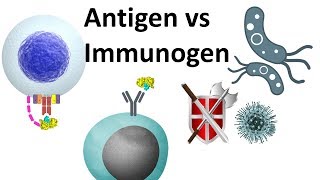

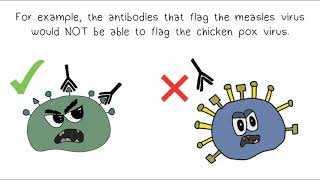

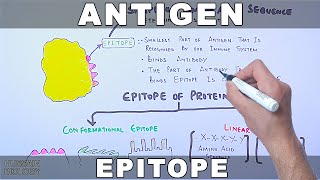

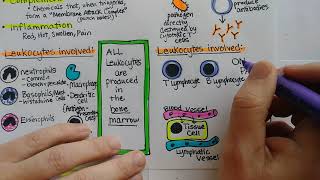

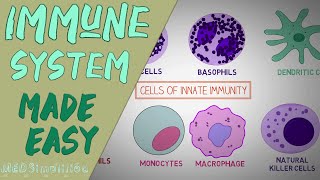

Adaptive Immunity

41. Immune System

Adaptive Immunity

Showing 10 of 10 videos

Additional 46 creators.

Learn with other creators

Showing 49 of 49 videos

Practice this topic

- Multiple ChoiceWhich of the following is a characteristic of adaptive immunity?1864views

- Multiple ChoiceWhy is HIV a dangerous pathogen?1806views

- Multiple ChoiceWhy does our immune system not usually attack our own healthy tissues?1748views

- Multiple ChoiceNew flu shots are needed every year to protect against infection because of __________.1304views