[crickets] [cymbal plays] [chime] [music plays] [CARROLL:] From jungle to desert, from forest to plain, from mountaintops to the sea shore, the Earth is home to many habitats. And every habitat contains a community of plants and animals. Each community is populated by different species. And each species is present in different numbers. [CARROLL (narrated):] So what determines how many species live in a given place? Or how large each population can grow? [CARROLL:] The answers to such basic questions about how nature works eluded biologists for a long time. Until on this rocky Pacific shore in 1963, young zoology professor Robert Paine pried a purple starfish off the rocks and threw it out into the bay. And so began one of the most important experiments in the history of ecology. [music plays] [CARROLL (narrated):] So what brought Robert Paine to this rugged coast? And why was he hurling starfish? The answer takes us back a few years to a classroom at the University of Michigan [PAINE:] It was a lovely day. The old zoology building in Ann Arbor had a courtyard. In that courtyard, there was a tree which was beginning to bud out. [CARROLL (narrated):] Professor Fred Smith asked his students a seemingly simple question. [PAINE:] And he said "Class, I want you to think about this... Why is that tree green?" And someone said... [FEMALE STUDENT:] Chlorophyll. [PAINE:] Fred said, "What keeps the leaves there?" [CARROLL (narrated):] Although technically, chlorophyll is what makes trees green, Fred Smith was asking a bigger question. He was thinking about food chains. [PAINE:] You obviously had producers. They are the energy suppliers to whatever lives off of them. Then you have consumers on top of that, and then, we know, the herbivores. [CARROLL (narrated):] The popular idea at the time was that the number of producers limits the number of herbivores. In turn the number of herbivores limits the number of predators that feed on them. Every level was regulated by the amount of food from the bottom of the food chain going up. But this view didn't explain why herbivore populations don't simply grow to the point where they eat all the leaves on the tree. Professor Smith had discussed this conundrum with two colleagues: Nelson Hairston and Lawrence Slobodkin. They proposed a new idea. The number of herbivores must be controlled not only from the bottom up, but also from the top down. [PAINE:] The herbivores had the capacity of destroying the plant community. Trees could be defoliated, and why weren't they defoliated? And the answer was, because there weren't enough insects around to do that, and that was the role of predators. [CARROLL (narrated):] The world is green because predators keep herbivores in check. This was a radical concept that became known as the "Green World Hypothesis." Up until that time, no one thought predators had any role in regulating ecosystems. [PAINE:] His class was the first public vetting of the Green World Hypothesis. [CARROLL (narrated):] And one of Smith's students, Robert Paine, would be the one to put this idea to the test. [music plays] A few years later, as a new professor at the University of Washington, Paine went looking for a system where he could study the role of predators. [PAINE:] I discovered the Pacific Ocean, and this magnificent array of organisms which lives along its margins. There it was, spread out in front of me. It was nirvana. [CARROLL (narrated):] He began by identifying all the organisms. And then he started mapping out who eats who. [PAINE:] There were carnivorous gastropods feeding on barnacles. There were sea urchins feeding on algae. There was a lot of pattern. [CARROLL (narrated):] His observations showed that a species of large, purple and orange starfish, called Pisaster ochraceus, was at the top of the food chain. [dramatic music] Starfish may seem like unlikely predators, but speed time up a bit and you'll see deadly hunters. [PAINE:] If a starfish is feeding, you turn it over and you see what the starfish is eating. They were eating mussels. They were eating a lot of other things as well, but they were eating mussels... [CARROLL (narrated):] So Paine asked, what happens when you remove the predator starfish from a single outcrop? [PAINE:] You have to surprise them, because a starfish clamps down. It takes a strong wrist and a pry bar. I would then scale them as I could, and in those days, I could throw a starfish 60 or 70 feet, out into deeper water. There were always starfish marching in, so during the summer months, I would drive the 350 miles round-trip, hit the area at low tide, do my removals, take other data, and then return to Seattle. [CARROLL (narrated):] The ecosystem started to change rapidly. [PAINE:] Within a year and a half, I knew that I hit ecological gold. [CARROLL (narrated):] Although the top predator had been removed, surprisingly, the number of species on the rock actually decreased from 15 to 8. [PAINE:] After three years, it went down to seven. But then by another seven years, it simplified itself 'til it was basically a monoculture. I'd changed the nature of the system. [CARROLL (narrated):] As the experiment continued, the line of mussels advanced down the rock face, monopolizing almost all of the available space, and pushing all other species out. Paine had discovered that one predator could regulate the composition of an entire community. He coined a term to describe the power a single species can exert on an ecosystem. [PAINE:] I know very little about architecture, but if you build an arch, you have to get the two sides of it to put pressure against one another, and therefore, at the apex of the arch you have a keystone. You pull the keystone out, and the structure collapses. [CARROLL (narrated):] Many predators, like Pisaster starfish, turn out to be keystone species. [PAINE:] These keystone species have a huge impact which extends well beyond the species they primarily prey on. [CARROLL (narrated):] Most species do not have large impacts. In other experiments, Paine had removed various species, but that had little or no effect on the ecosystem as a whole. [PAINE:] "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others." And that expresses the fact that all species don't have the same impact on the system they're in. It takes experiments to tease that out, and that's often not easily done. [CARROLL (narrated):] Paine's pioneering experiments and the concept of keystone species, sent ripples through the field of ecology, and turned thinking about the regulation of communities upside down. [PAINE:] You remove the predator, the system simplifies itself. This is an ecological concept which is general and global. [CARROLL (narrated):] As Paine continued his studies a little further from shore, he noticed another striking pattern. [PAINE:] There were a lot of tide pools. And some of the tide pools were dominated by urchins, some weren't. [CARROLL (narrated):] In the tide pools with lots of urchins, there was much less kelp. Paine suspected the urchins were keeping the kelp from growing. [PAINE:] And I said to myself, that's my next round of experiments. [CARROLL (narrated):] Paine removed all the urchins by hand from some pools and left nearby pools untouched. Again, the results were dramatic. In the pools where he removed urchins, the kelp started growing almost immediately. [PAINE:] Urchins control the kelp; therefore, it's a total violation of the Green World Hypothesis. [CARROLL (narrated):] The urchins in Paine's pools were eating all of the kelp. So why was nothing regulating the urchin populations? The answer would come from a fortuitous meeting, on a remote island in Alaska's Aleutian Island chain. There, Paine would cross paths with another scientist. In 1971, James Estes was an ambitious young graduate student. [ESTES:] At the time that Bob and I met, I was just beginning to try to think my way through what it was I was going to do. [PAINE:] We met in a bar after a movie. I was interested in sea urchins and Jim, I think, was doing a study on sea otter physiology. [ESTES:] I was explaining to him what it was that I was thinking of trying to do, which was somehow understand how an ecosystem like the one at Amchitka Island could support such a high abundance of predators, and do that through an understanding of production and the efficiency of energy and material flow upward through the food web. And Bob's explicit or implicit reaction to that was "that's just not very interesting." And "have you ever thought about what these animals might be doing to the system?" [CARROLL (narrated):] Paine realized if Estes focused on what sea otters were doing from the top down, rather than the kelp from the bottom up, he might discover the role otters play in the organization of nature. [ESTES:] And so I thought, why not? Let's go out and have a look. [CARROLL (narrated):] Paine was suggesting an approach similar to his starfish-throwing experiment: Remove otters from the ecosystem and test the impact that had on other species. [ESTES:] I don't think at that time that Bob had any perception of how that might be done. But I did, because I knew quite a bit about the history of the otters. They were abundant across the North Pacific. And then the Pacific Maritime fur trade began in 1741, and over the subsequent 150 years, otters were hunted to the brink of extinction. In 1911 or 1912, further take was prohibited, and a few of those colonies survived and served as the seed for the recovery of the species. [CARROLL (narrated):] But the sea otter recovery was spotty. [ESTES:] They had completely recovered from the fur trade at a number of island systems across the Aleutian archipelago, of which Amchitka is a part. There were other island systems where they had not yet recovered. [CARROLL (narrated):] The experiment was simple: Compare ecosystems with otters to those without. He began with his home island of Amchitka. [ESTES:] I knew a lot about what Amchitka looked like. I knew that sea urchins were common but very small. [CARROLL (narrated):] The next step was to arrange for a dive at nearby Shemya Island, a location with no otters. [ESTES:] The most dramatic moment of learning in my life happened in less than a second. And that was sticking my head in the water at Shemya Island. It was just green with urchins and no kelp. And it all sort of fell into place in just an instant, that the loss of otters from that system had completely reorganized that system from which kelps had probably been very abundant before the loss of otters, to one in which the sea urchins now had become abundant in the absence of the otters and had eaten all the kelp. [CARROLL (narrated):] It was a striking demonstration of the Green World Hypothesis. Sea otters, the predators, were controlling the urchins that fed on the kelp. Remove the sea otters and the kelp forests disappear. Paine called these cascading effects of one species downward upon others "trophic cascades." [PAINE:] A trophic cascade is when you have an apex predator controlling the distribution of resources, and they lead to these cascades of indirect effects. Lots and lots of indirect effects. You have fewer sea otters, you have more sea urchins, you have fewer kelp. [ESTES:] I expect every coastal species is probably impacted in one way or another by the presence or absence of kelp. Kelp forest fishes depend a lot on kelp. There are birds that feed in the kelp forests, there are invertebrates that feed in the kelp forest. Virtually everything that lives in the coastal zone depends upon that system in some way. [CARROLL (narrated):] So sea otters are another keystone species. They regulate the structure of this coastal marine community. [ESTES:] The results are unambiguous. Sea otters drive this system from the top down. You know, the message is clear, and it's been enormously important in how ecologists tend to view the world. [CARROLL (narrated):] Estes returned regularly to Alaska to study otters. Some twenty years later, he noticed something strange was happening. [ESTES:] We were capturing otters, having a devil of a time catching enough, and that was peculiar, because I'd never had trouble catching otters. [CARROLL (narrated):] Otter populations seemed to be declining. He tried to think of every possible explanation. [ESTES:] And we essentially lined up all of the hypotheses that we could think of that could be causing this population decline. [CARROLL (narrated):] He ruled out starvation. He ruled out disease. And then a third hypothesis emerged. [ESTES:] Tim Tinker, who is a technician, called me one day in the winter and said, "you know, I'm starting to wonder if it might be killer whales." And I said, "you're crazy. You know, I mean, this just couldn't happen. They don't eat otters." And he said, "yes, they do. I've seen them eat a couple." [CARROLL (narrated):] But how could he test it? Once again, nature provided an ideal site. [ESTES:] We went into a place called Clam Lagoon. It provided us a site that orcas could not get to. We had no problem catching about 30 animals in two or three days. And the fact that that little population did not decline when everything else did that orcas had access to, helped me become convinced that it was a viable hypothesis. [CARROLL (narrated):] Why were the orcas now eating otters? Orcas generally eat whales, not otters. [ESTES:] There were a lot of whales around after World War II. After World War II, the Japanese and the Russians started reducing those whales, and by the late 1960s, they had been depleted by 90%. And the stripping of all these big whales out of the system shocked these killer whales and forced them to broaden their diet and start feeding on these other species. What had happened is that we had taken this three-level trophic cascade and the orcas had added a fourth trophic level, and it made that system behave just like theory predicted. [CARROLL (narrated):] With the orcas eating otters, urchin populations increased and kelp disappeared. [ESTES:] To me, the amazing part of that was the notion that something like whaling, that started in the middle of the 20th century, way out in the oceanic realm of the North Pacific, could affect something like urchins and kelp in the coastal ecosystem. It was mind-boggling to even conceive of something... it was almost like science fiction. [CARROLL (narrated):] To Robert Paine, this was a satisfying confirmation. [PAINE:] It provided an example of how the concept of a trophic cascade functions in nature, and it's Jim's work in the Aleutians which in fact sold the case. [CARROLL:] As ecologists explored other habitats with new eyes, they discovered keystone species and trophic cascades in many places. [CARROLL (narrated):] And just as with otters, the removal of predators, such as wolves, sharks, and lions, has had profound effects on the number and variety of other species, and on ecosystems as a whole. These fundamental insights have changed the way we look at the world. And they've given ecologists and conservationists a new set of tools. [ESTES:] It has turned us from a fundamental view of nature that was bottom-up. More than any other single ecologist, he was the one that transitioned our thinking to the importance of top-down forcing. [PAINE:] Well, thank you. [ESTES:] No, it's the truth. [CARROLL (narrated):] But from Paine's vantage point, humans still have much to learn. [PAINE:] To ignore the fact that there are top-down effects is to invite mistakes. One ignores at one's own risk what role apex predators play. [wolf howls] [music plays]

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction to Biology2h 40m

- 2. Chemistry3h 40m

- 3. Water1h 26m

- 4. Biomolecules2h 23m

- 5. Cell Components2h 26m

- 6. The Membrane2h 31m

- 7. Energy and Metabolism2h 0m

- 8. Respiration2h 40m

- 9. Photosynthesis2h 49m

- 10. Cell Signaling59m

- 11. Cell Division2h 47m

- 12. Meiosis2h 0m

- 13. Mendelian Genetics4h 44m

- Introduction to Mendel's Experiments7m

- Genotype vs. Phenotype17m

- Punnett Squares13m

- Mendel's Experiments26m

- Mendel's Laws18m

- Monohybrid Crosses19m

- Test Crosses14m

- Dihybrid Crosses20m

- Punnett Square Probability26m

- Incomplete Dominance vs. Codominance20m

- Epistasis7m

- Non-Mendelian Genetics12m

- Pedigrees6m

- Autosomal Inheritance21m

- Sex-Linked Inheritance43m

- X-Inactivation9m

- 14. DNA Synthesis2h 27m

- 15. Gene Expression3h 20m

- 16. Regulation of Expression3h 31m

- Introduction to Regulation of Gene Expression13m

- Prokaryotic Gene Regulation via Operons27m

- The Lac Operon21m

- Glucose's Impact on Lac Operon25m

- The Trp Operon20m

- Review of the Lac Operon & Trp Operon11m

- Introduction to Eukaryotic Gene Regulation9m

- Eukaryotic Chromatin Modifications16m

- Eukaryotic Transcriptional Control22m

- Eukaryotic Post-Transcriptional Regulation28m

- Eukaryotic Post-Translational Regulation13m

- 17. Viruses37m

- 18. Biotechnology2h 58m

- 19. Genomics17m

- 20. Development1h 5m

- 21. Evolution3h 1m

- 22. Evolution of Populations3h 52m

- 23. Speciation1h 37m

- 24. History of Life on Earth2h 6m

- 25. Phylogeny2h 31m

- 26. Prokaryotes4h 59m

- 27. Protists1h 12m

- 28. Plants1h 22m

- 29. Fungi36m

- 30. Overview of Animals34m

- 31. Invertebrates1h 2m

- 32. Vertebrates50m

- 33. Plant Anatomy1h 3m

- 34. Vascular Plant Transport2m

- 35. Soil37m

- 36. Plant Reproduction47m

- 37. Plant Sensation and Response1h 9m

- 38. Animal Form and Function1h 19m

- 39. Digestive System10m

- 40. Circulatory System1h 57m

- 41. Immune System1h 12m

- 42. Osmoregulation and Excretion50m

- 43. Endocrine System4m

- 44. Animal Reproduction2m

- 45. Nervous System55m

- 46. Sensory Systems46m

- 47. Muscle Systems23m

- 48. Ecology3h 11m

- Introduction to Ecology20m

- Biogeography14m

- Earth's Climate Patterns50m

- Introduction to Terrestrial Biomes10m

- Terrestrial Biomes: Near Equator13m

- Terrestrial Biomes: Temperate Regions10m

- Terrestrial Biomes: Northern Regions15m

- Introduction to Aquatic Biomes27m

- Freshwater Aquatic Biomes14m

- Marine Aquatic Biomes13m

- 49. Animal Behavior28m

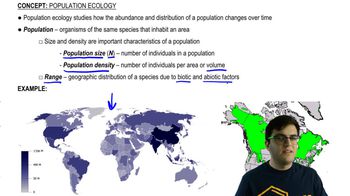

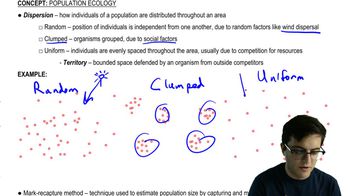

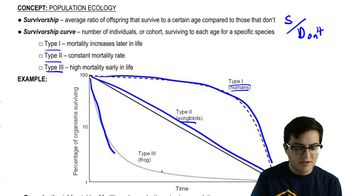

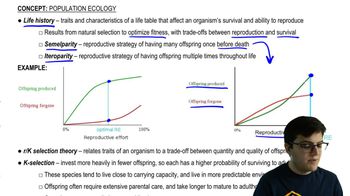

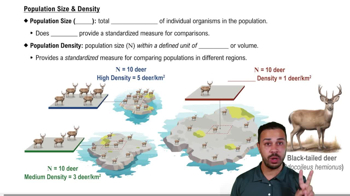

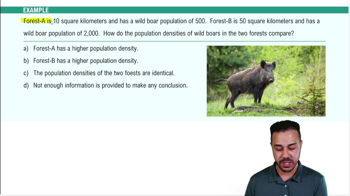

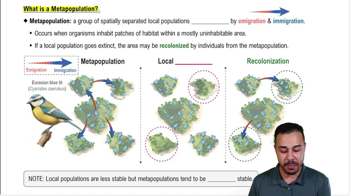

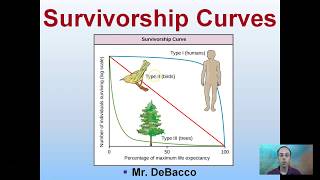

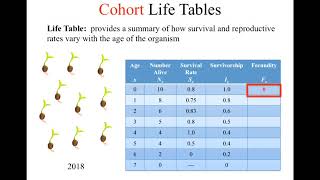

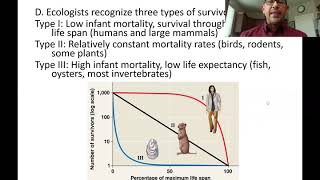

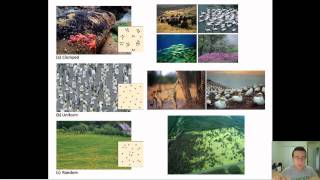

- 50. Population Ecology3h 41m

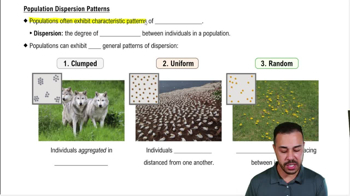

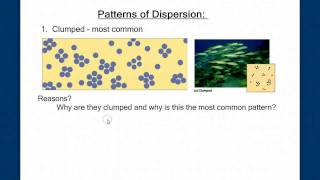

- Introduction to Population Ecology28m

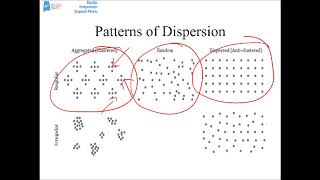

- Population Sampling Methods23m

- Life History12m

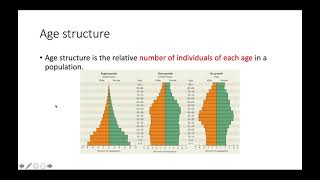

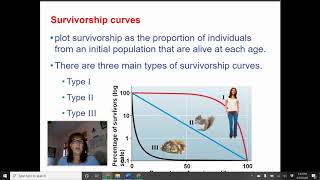

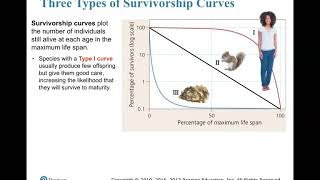

- Population Demography17m

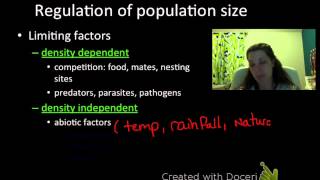

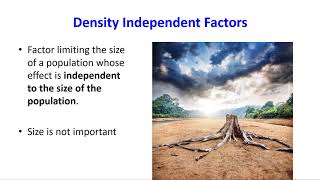

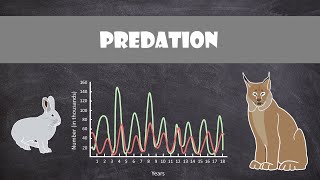

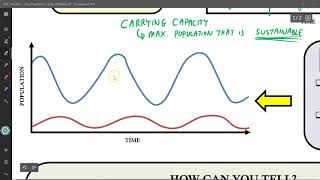

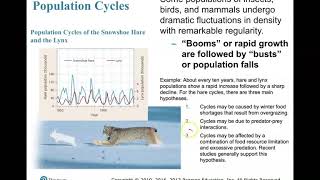

- Factors Limiting Population Growth14m

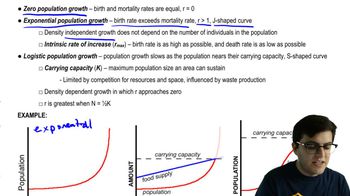

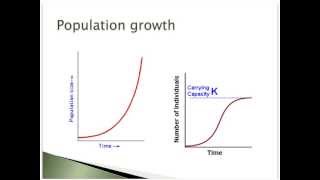

- Introduction to Population Growth Models22m

- Linear Population Growth6m

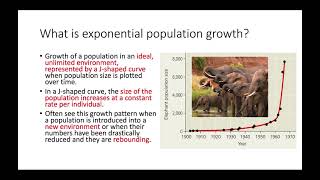

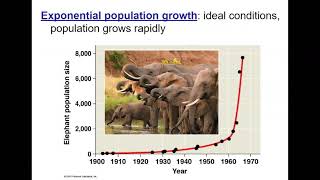

- Exponential Population Growth29m

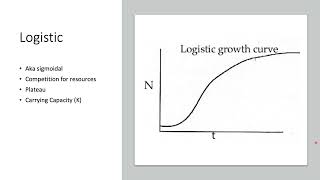

- Logistic Population Growth32m

- r/K Selection10m

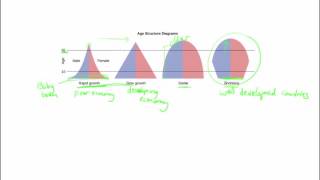

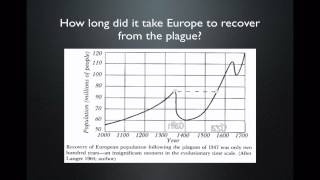

- The Human Population22m

- 51. Community Ecology2h 46m

- Introduction to Community Ecology2m

- Introduction to Community Interactions9m

- Community Interactions: Competition (-/-)38m

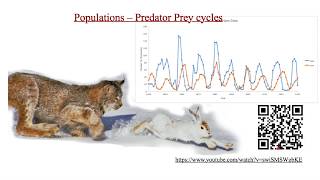

- Community Interactions: Exploitation (+/-)23m

- Community Interactions: Mutualism (+/+) & Commensalism (+/0)9m

- Community Structure35m

- Community Dynamics26m

- Geographic Impact on Communities21m

- 52. Ecosystems2h 36m

- 53. Conservation Biology24m

50. Population Ecology

Introduction to Population Ecology

Video duration:

19mPlay a video:

Related Videos

Related Practice