Table of contents

- 1. Introduction to Anatomy & Physiology5h 43m

- What is Anatomy & Physiology?22m

- Levels of Organization13m

- Variation in Anatomy & Physiology12m

- Introduction to Organ Systems27m

- Homeostasis10m

- Feedback Loops11m

- Feedback Loops: Negative Feedback19m

- Feedback Loops: Positive Feedback11m

- Anatomical Position7m

- Introduction to Directional Terms3m

- Directional Terms: Up and Down9m

- Directional Terms: Front and Back6m

- Directional Terms: Body Sides12m

- Directional Terms: Limbs6m

- Directional Terms: Depth Within the Body4m

- Introduction to Anatomical Terms for Body Regions3m

- Anatomical Terms for the Head and Neck8m

- Anatomical Terms for the Front of the Trunk8m

- Anatomical Terms for the Back9m

- Anatomical Terms for the Arm and Hand9m

- Anatomical Terms for the Leg and Foot15m

- Review- Using Anatomical Terms and Directions12m

- Abdominopelvic Quadrants and Regions19m

- Anatomical Planes & Sections17m

- Organization of the Body: Body Cavities13m

- Organization of the Body: Serous Membranes14m

- Organization of the Body: Serous Membrane Locations8m

- Organization of the Body: Thoracic Cavity8m

- Organization of the Body: Abdominopelvic Cavity12m

- 2. Cell Chemistry & Cell Components12h 36m

- Atoms- Smallest Unit of Matter57m

- Isotopes37m

- Introduction to Chemical Bonding19m

- Covalent Bonds40m

- Noncovalent Bonds5m

- Ionic Bonding37m

- Hydrogen Bonding19m

- Introduction to Water7m

- Properties of Water- Cohesion and Adhesion7m

- Properties of Water- Density8m

- Properties of Water- Thermal14m

- Properties of Water- The Universal Solvent17m

- Acids and Bases12m

- pH Scale21m

- Carbon8m

- Functional Groups9m

- Introduction to Biomolecules2m

- Monomers & Polymers11m

- Carbohydrates23m

- Proteins28m

- Nucleic Acids34m

- Lipids28m

- Microscopes11m

- Prokaryotic & Eukaryotic Cells26m

- Introduction to Eukaryotic Organelles14m

- Endomembrane System: Protein Secretion30m

- Endomembrane System: Digestive Organelles14m

- Mitochondria & Chloroplasts21m

- Endosymbiotic Theory10m

- Introduction to the Cytoskeleton11m

- Cell Junctions8m

- Biological Membranes11m

- Types of Membrane Proteins8m

- Concentration Gradients and Diffusion9m

- Introduction to Membrane Transport16m

- Passive vs. Active Transport14m

- Osmosis30m

- Simple and Facilitated Diffusion17m

- Active Transport30m

- Endocytosis and Exocytosis15m

- 3. Energy & Cell Processes10h 8m

- Introduction to Energy15m

- Laws of Thermodynamics15m

- Chemical Reactions9m

- ATP22m

- Enzymes14m

- Enzyme Activation Energy9m

- Enzyme Binding Factors9m

- Enzyme Inhibition10m

- Introduction to Metabolism8m

- Redox Reactions15m

- Introduction to Cellular Respiration22m

- Types of Phosphorylation14m

- Glycolysis19m

- Pyruvate Oxidation8m

- Krebs Cycle16m

- Electron Transport Chain10m

- Chemiosmosis7m

- Review of Aerobic Cellular Respiration19m

- Fermentation & Anaerobic Respiration23m

- Introduction to Cell Division22m

- Organization of DNA in the Cell17m

- Introduction to the Cell Cycle7m

- Interphase18m

- Phases of Mitosis48m

- Cytokinesis16m

- Cell Cycle Regulation18m

- Review of the Cell Cycle7m

- Cancer13m

- Introduction to DNA Replication22m

- DNA Repair8m

- Central Dogma7m

- Introduction to Transcription20m

- Steps of Transcription19m

- Genetic Code25m

- Introduction to Translation30m

- Steps of Translation23m

- Post-Translational Modification6m

- 4. Tissues & Histology10h 3m

- Introduction to Tissues & Histology16m

- Introduction to Epithelial Tissue24m

- Characteristics of Epithelial Tissue37m

- Structural Naming of Epithelial Tissue19m

- Simple Epithelial Tissues1h 2m

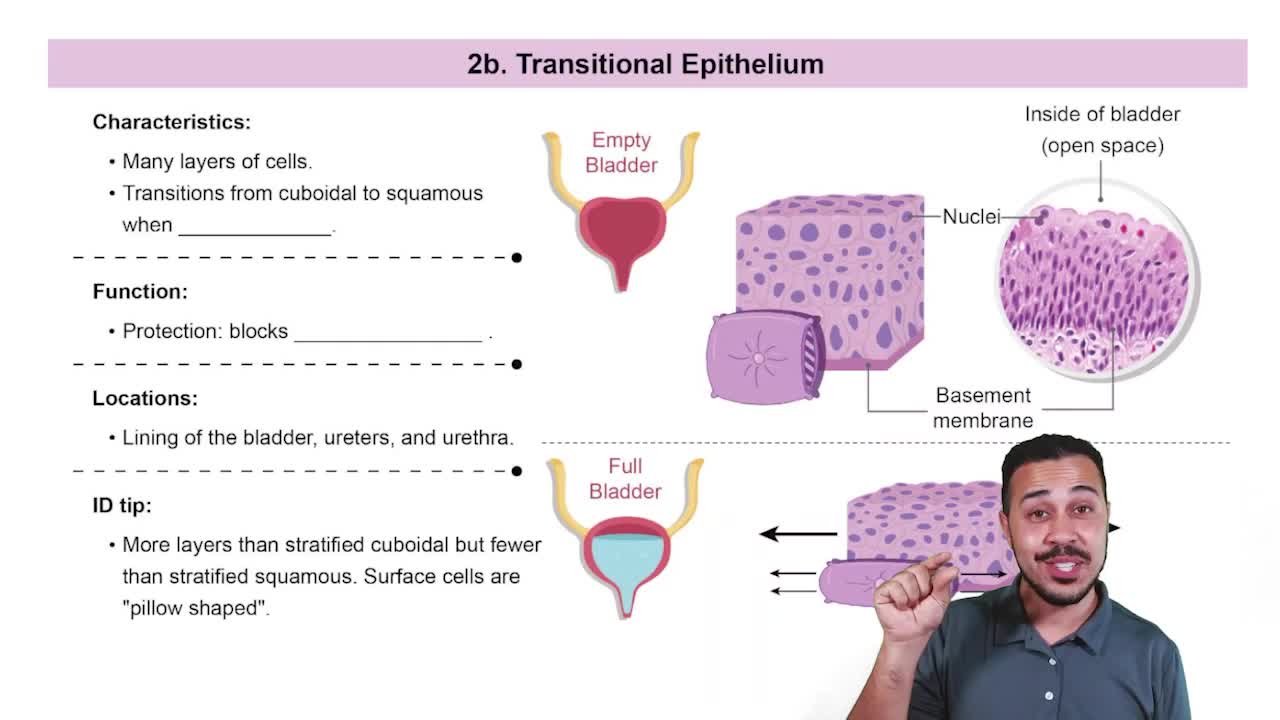

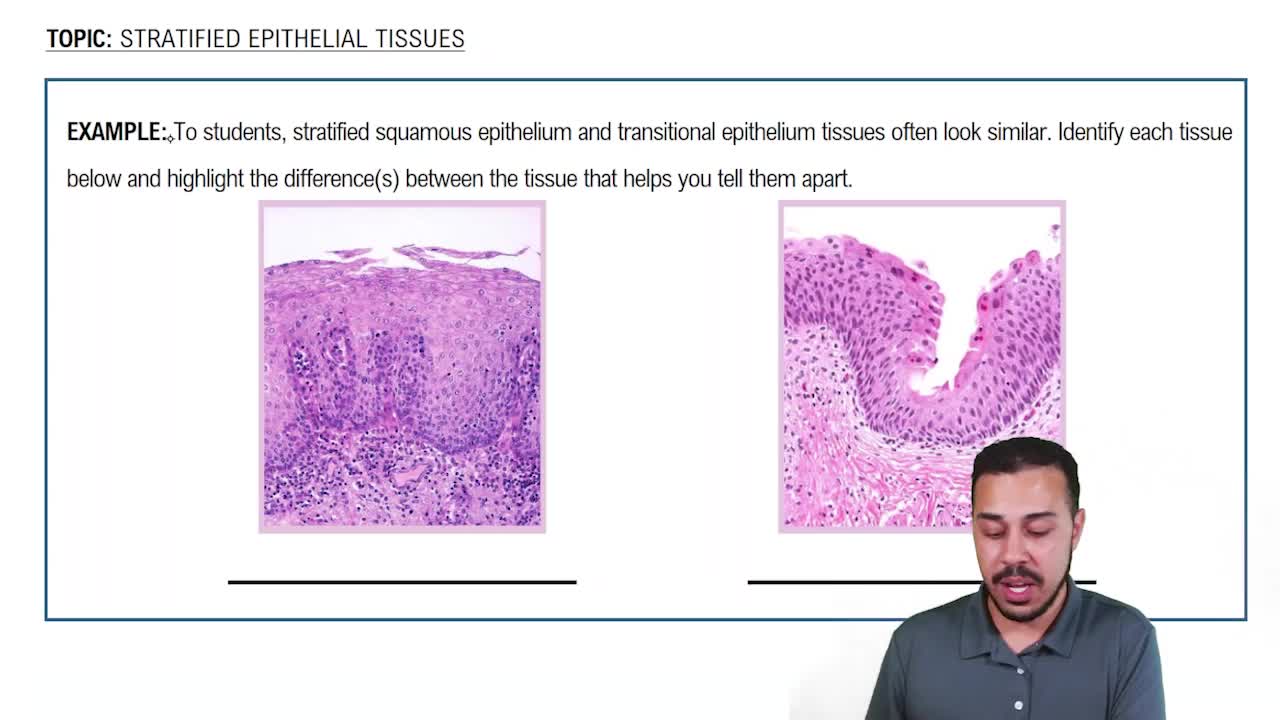

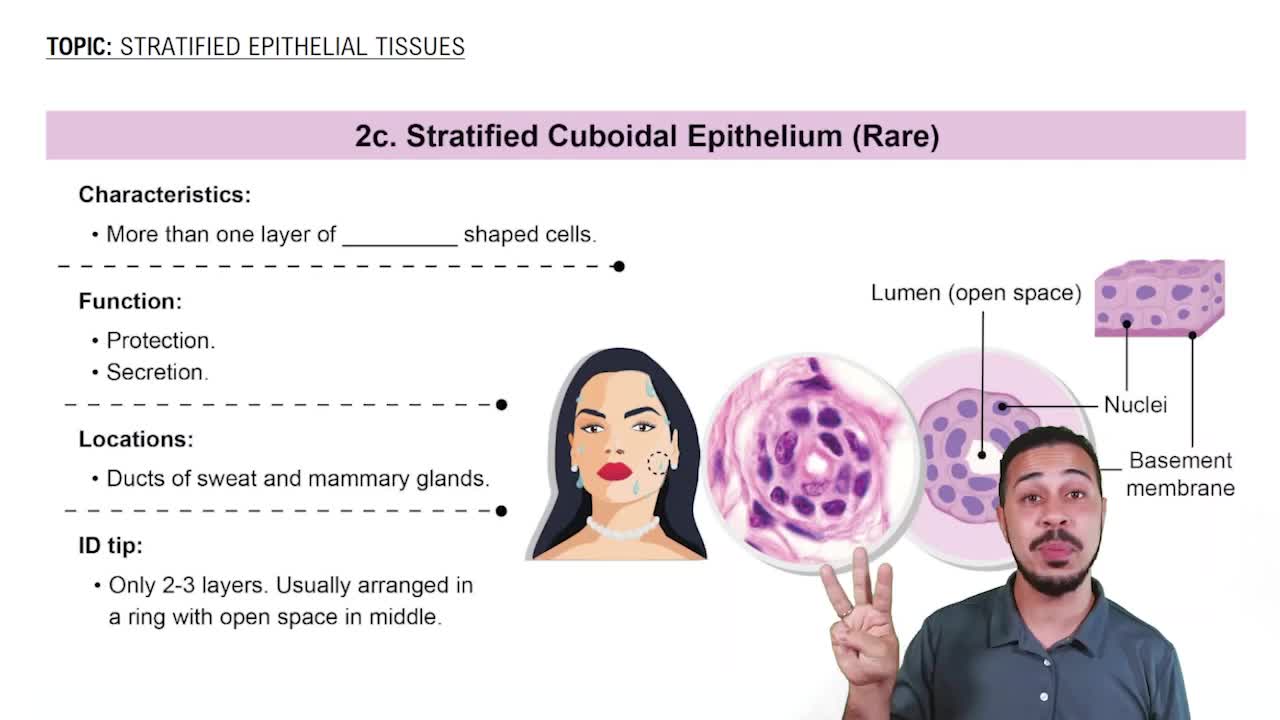

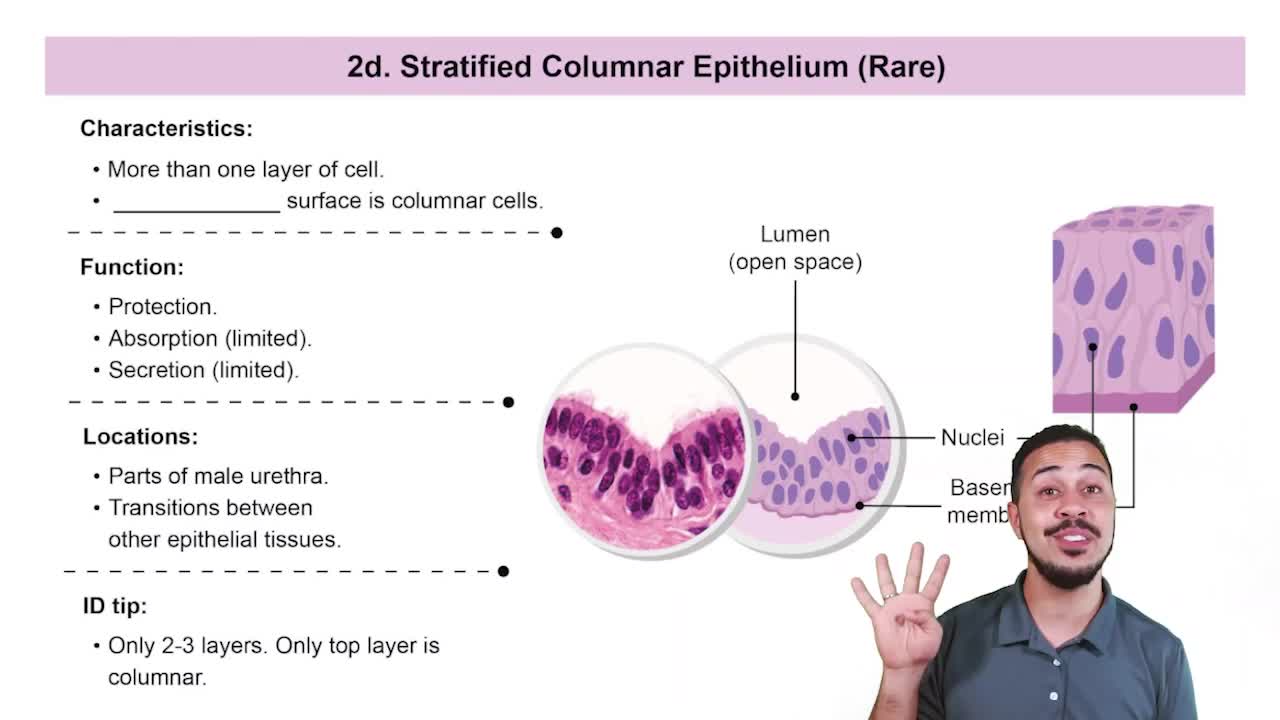

- Stratified Epithelial Tissues55m

- Identifying Types of Epithelial Tissue32m

- Glandular Epithelial Tissue26m

- Introduction to Connective Tissue36m

- Classes of Connective Tissue8m

- Introduction to Connective Tissue Proper40m

- Connective Tissue Proper: Loose Connective Tissue56m

- Connective Tissue Proper: Dense Connective Tissue49m

- Specialized Connective Tissue: Cartilage44m

- Specialized Connective Tissue: Bone12m

- Specialized Connective Tissue: Blood9m

- Introduction to Muscle Tissue7m

- Types of Muscle Tissue45m

- Introduction to Nervous Tissue8m

- Nervous Tissue: The Neuron8m

- 5. Integumentary System2h 28m

- 6. Bones & Skeletal Tissue2h 16m

- An Introduction to Bone and Skeletal Tissue18m

- Gross Anatomy of Bone: Compact and Spongy Bone7m

- Gross Anatomy of Bone: Periosteum and Endosteum11m

- Gross Anatomy of Bone: Bone Marrow8m

- Gross Anatomy of Bone: Short, Flat, and Irregular Bones5m

- Gross Anatomy of Bones - Structure of a Long Bone23m

- Microscopic Anatomy of Bones - Bone Matrix9m

- Microscopic Anatomy of Bones - Bone Cells25m

- Microscopic Anatomy of Bones - The Osteon17m

- Microscopic Anatomy of Bones - Trabeculae9m

- 7. The Skeletal System2h 35m

- 8. Joints2h 17m

- 9. Muscle Tissue2h 33m

- 10. Muscles1h 11m

- 11. Nervous Tissue and Nervous System1h 35m

- 12. The Central Nervous System1h 6m

- 13. The Peripheral Nervous System1h 26m

- Introduction to the Peripheral Nervous System5m

- Organization of Sensory Pathways16m

- Introduction to Sensory Receptors5m

- Sensory Receptor Classification by Modality6m

- Sensory Receptor Classification by Location8m

- Proprioceptors7m

- Adaptation of Sensory Receptors8m

- Introduction to Reflex Arcs13m

- Reflex Arcs15m

- 14. The Autonomic Nervous System1h 38m

- 15. The Special Senses2h 41m

- 16. The Endocrine System2h 47m

- 17. The Blood3h 22m

- 18. The Heart3h 42m

- 19. The Blood Vessels3h 35m

- 20. The Lymphatic System3h 16m

- 21. The Immune System14h 37m

- Introduction to the Immune System10m

- Introduction to Innate Immunity17m

- Introduction to First-Line Defenses5m

- Physical Barriers in First-Line Defenses: Skin13m

- Physical Barriers in First-Line Defenses: Mucous Membrane9m

- First-Line Defenses: Chemical Barriers24m

- First-Line Defenses: Normal Microbiota7m

- Introduction to Cells of the Immune System15m

- Cells of the Immune System: Granulocytes28m

- Cells of the Immune System: Agranulocytes26m

- Introduction to Cell Communication5m

- Cell Communication: Surface Receptors & Adhesion Molecules16m

- Cell Communication: Cytokines27m

- Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs)48m

- Introduction to the Complement System24m

- Activation Pathways of the Complement System23m

- Effects of the Complement System23m

- Review of the Complement System13m

- Phagocytosis17m

- Introduction to Inflammation18m

- Steps of the Inflammatory Response28m

- Fever8m

- Interferon Response25m

- Review Map of Innate Immunity

- Introduction to Adaptive Immunity32m

- Antigens12m

- Introduction to T Lymphocytes38m

- Major Histocompatibility Complex Molecules20m

- Activation of T Lymphocytes21m

- Functions of T Lymphocytes25m

- Review of Cytotoxic vs Helper T Cells13m

- Introduction to B Lymphocytes27m

- Antibodies14m

- Classes of Antibodies35m

- Outcomes of Antibody Binding to Antigen15m

- T Dependent & T Independent Antigens21m

- Clonal Selection20m

- Antibody Class Switching17m

- Affinity Maturation14m

- Primary and Secondary Response of Adaptive Immunity21m

- Immune Tolerance28m

- Regulatory T Cells10m

- Natural Killer Cells16m

- Review of Adaptive Immunity25m

- 22. The Respiratory System3h 20m

- 23. The Digestive System3h 5m

- 24. Metabolism and Nutrition4h 0m

- Essential Amino Acids5m

- Lipid Vitamins19m

- Cellular Respiration: Redox Reactions15m

- Introduction to Cellular Respiration22m

- Cellular Respiration: Types of Phosphorylation14m

- Cellular Respiration: Glycolysis19m

- Cellular Respiration: Pyruvate Oxidation8m

- Cellular Respiration: Krebs Cycle16m

- Cellular Respiration: Electron Transport Chain14m

- Cellular Respiration: Chemiosmosis7m

- Review of Aerobic Cellular Respiration18m

- Fermentation & Anaerobic Respiration23m

- Gluconeogenesis16m

- Fatty Acid Oxidation20m

- Amino Acid Oxidation17m

- 25. The Urinary System2h 39m

- 26. Fluid and Electrolyte Balance, Acid Base Balance37m

- 27. The Reproductive System2h 5m

- 28. Human Development1h 21m

- 29. Heredity3h 32m

4. Tissues & Histology

Stratified Epithelial Tissues

Stratified Squamous Epithelia

Bruce Bryan

Video duration:

11mPlay a video:

Related Videos

Related Practice