Prokaryotes, bacteria, and archaea make up 60% of Earth's biomass. And by that, I mean, if you took all the living organisms of Earth and you put them on a scale, right, 60% of the weight that you'd be reading on that scale would be due to prokaryotic cells, right? These little microscopic organisms. They were the first life forms, and they also happen to be the most prolific. They're everywhere. I mean, they're inside us, they're on our skin, they're inside other creatures. If you take a scoop of ocean water, you're going to get a ton of them in there. I mean, these guys are everywhere. And they're also in crazy places too, like deep sea hydrothermal vents. They're just amazing organisms. And the reason I'm saying all of this is because it is, in a sense, tragic how little we really get to talk about them in introductory biology. Okay? So we're doing a quick review of them here, but by no means, should you take that as an indication that these are unimportant or uninteresting organisms. They're actually some of the most important, most interesting life forms on the planet. Introductory biology just tends to be a little more focused on the type of organisms that, you know, humans interact or visibly interact with on a day-to-day basis. Okay? So take microbiology, it's truly fascinating.

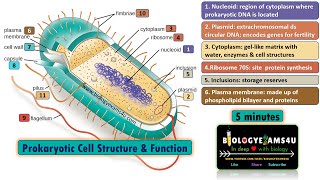

And now, we are going to briefly, you know, in an almost criminally briefly discuss archaea, which are prokaryotes similar to bacteria, but they have certain features that differentiate them from bacteria and of course, eukaryotes. So they're of a similar size and shape to bacteria. But unlike bacteria, they do not use peptidoglycan in their cell walls. The chemical composition of their membranes is distinct from both bacteria and eukaryotes. Now, just like bacteria, they have a circular loop of DNA. Right? That's their chromosome. You'll find it in a nucleoid in the cell. They also lack membrane-bound organelles and a nucleus. Right? So they are, you know, prokaryotes, they have all those defining prokaryotic features. However, there are some interesting differences between them and bacteria. For one, their genetic machinery that they use for transcription and translation, right, gene expression, happens to be more similar to eukaryotes than to bacteria. Which is pretty fascinating and it's also one of the reasons that eukaryotes are thought to have evolved from archaea not bacteria.

Additionally, archaea reproduce asexually similar to bacteria, but like bacteria, they're capable of forms of gene transfer and, we're going to get into how that works in a different video. So the takeaway is archaea are similar to bacteria, but there are some biochemical differences that separate them as a class of organism. Now the thing most people tend to know about archaea is that they're extremophiles, but this is actually anecdotal. I mean, certainly, there are many species of extremophiles within archaea, but there are many, many types of archaea that don't live in extreme environments. Right?

Really the whole 'archaea or extremophiles' is not a good generalization. Now looking at this image here, these are some really famous archaea which you will find in Yellowstone. This is what's known as the Grand Prismatic Pool. It is a sulfur-rich hot spring, and the archaea that live in there are known as thermophiles. Right? They like heat. And they will live in these hot springs, which are, you know, close to boiling point roughly. They can also be found in these deep sea hydrothermal vents that exude incredibly hot temperatures. I mean, way beyond boiling point. Right? So, they don't all just like the most extreme temperatures. They like a range of temperatures. And that's really the point I'm trying to impress in general is that archaea can be found in all different types of environments.

Some cool ones that I happen to like are the halophiles, and these like to live in salty environments, including environments as salty as the Dead Sea. Right? Which has such a high salinity level that, if you were to swim in it, you'd feel the difference in density of the water. You know, it just feels very thick. Now methanogens are a really cool type of archaea. They produce methane as a byproduct of their metabolism, and these are found all over the place. They live in swamps. Right? That's that kind of funky gross smell that you smell in swamps is, from methane in part, and that's due to methanogens. And also they live in the guts of animals. And, cows for example, or ruminants, have, these methanogens that live inside them, and that's, where, the methane that they fart comes from.

Last last thing I want to point out is, you know, main theme of biology, structure fits function. Right? So here we have the normal sort of phospholipid bilayer. Right? This is composed of, you know, what you can kind of think of as like generic or vanilla phospholipids. Right? And this you'll find in, you know, regular old prokaryotes, eukaryotes, whatever. Here, on the other hand, we have our phospholipids from the hot spring bacteria, and you'll notice that the actual chemical structure of these is pretty different. Right? And it's made of these isoprene units. That's what these are called. Don't worry about the name. The main point is, these phospholipids will stick together much more tightly, which is how the membranes of these hot spring prokaryotes will resist breaking down at those high temperatures. So again, like structure fits function and you're going to see these biochemical differences between the cells of archaea and the cells of bacteria. Alright. That's all I have for this video. See you guys later.