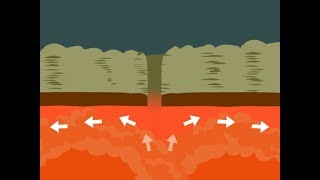

Now, because of continental drift, the distribution of organisms and ecosystems across the continents has shifted over time as continents break apart. As these continents separate and ecosystems and species become divided, they are influenced by different evolutionary forces and therefore follow different evolutionary pathways. We call the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and across geologic time biogeography. One can see an image trying to represent how certain species were distributed across continents and how, when those continents broke up, those species—the pockets and populations of that species—would be separated. Evolutionary forces would act differently upon them, resulting in different evolutionary courses. Our picture of the ancient world and the life on Earth before our time comes from the fossil record. The problem is that the fossil record is not only limited; it's biased. What does that mean, biased? Well, let's say that organism A lives in conditions that are very conducive to forming fossils. So, when organism A dies, there is a high chance that its body will be preserved as a fossil. Whereas, organism B lives in an environment where it's very likely that its body will be degraded when it dies, meaning there is a low chance that it would turn into a fossil. Due to this, millions and millions of years later, when humans are digging up fossils, we are much more likely to uncover a fossil of organism A than organism B. Not because there were more of organism A back in the day, but because organism A had a higher chance of dying and turning into a fossil. That example I just mentioned is an oversimplification and only illustrates one way that bias can arise in the fossil record. There are many other ways. However, it's important to note that the fossil record does not provide us with a complete picture of life on Earth. In fact, it offers a very limited snapshot of some of the things that used to exist.

We date fossils using radiocarbon dating, which we discussed in a previous lesson at the beginning of this course. Radiocarbon dating involves comparing the ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-14. The oldest fossil of a living organism, called a stromatolite, still exists today. Here we can see the fossil of a stromatolite, a structure created by photosynthetic cyanobacteria, sometimes called blue-green algae, though they are a type of bacteria, not algae. These stromatolites are formed by the metabolic processes of cyanobacteria as a byproduct of their metabolism, and they are still around today. As seen in a recent photo, these are stromatolites with living cyanobacteria. It's incredible that our oldest fossils of living organisms are actually things that still exist today that we can visit if we desire.

Getting back to radiocarbon dating, the ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-14 is crucial, especially when discussing the concept of half-life, which represents the time it takes for half of a sample to decay. To give a refresher on how this all works, let's consider that there is a small percentage of carbon in the environment that is an isotope called carbon-14. Most carbon is carbon-12, a very stable atom, which is why so many living things are made of it. Carbon-14, however, will decay and transform into a different element. For example, let's assume that 10% of all the carbon in the world is carbon-14. When an organism is alive, like myself, it incorporates carbon-14 regularly. Therefore, approximately 10% of the carbon in my body would be carbon-14. Once I die, carbon-14 incorporation ceases, and over time, such as a million years later, less than 10% of the carbon in my body would be carbon-14. With the known half-life of carbon-14 and the percentage of carbon-14 present in the environment, scientists can approximat