Table of contents

- 1. Introduction to Biology2h 42m

- 2. Chemistry3h 40m

- 3. Water1h 26m

- 4. Biomolecules2h 23m

- 5. Cell Components2h 26m

- 6. The Membrane2h 31m

- 7. Energy and Metabolism2h 0m

- 8. Respiration2h 40m

- 9. Photosynthesis2h 49m

- 10. Cell Signaling59m

- 11. Cell Division2h 47m

- 12. Meiosis2h 0m

- 13. Mendelian Genetics4h 44m

- Introduction to Mendel's Experiments7m

- Genotype vs. Phenotype17m

- Punnett Squares13m

- Mendel's Experiments26m

- Mendel's Laws18m

- Monohybrid Crosses19m

- Test Crosses14m

- Dihybrid Crosses20m

- Punnett Square Probability26m

- Incomplete Dominance vs. Codominance20m

- Epistasis7m

- Non-Mendelian Genetics12m

- Pedigrees6m

- Autosomal Inheritance21m

- Sex-Linked Inheritance43m

- X-Inactivation9m

- 14. DNA Synthesis2h 27m

- 15. Gene Expression3h 20m

- 16. Regulation of Expression3h 31m

- Introduction to Regulation of Gene Expression13m

- Prokaryotic Gene Regulation via Operons27m

- The Lac Operon21m

- Glucose's Impact on Lac Operon25m

- The Trp Operon20m

- Review of the Lac Operon & Trp Operon11m

- Introduction to Eukaryotic Gene Regulation9m

- Eukaryotic Chromatin Modifications16m

- Eukaryotic Transcriptional Control22m

- Eukaryotic Post-Transcriptional Regulation28m

- Eukaryotic Post-Translational Regulation13m

- 17. Viruses37m

- 18. Biotechnology2h 58m

- 19. Genomics17m

- 20. Development1h 5m

- 21. Evolution3h 1m

- 22. Evolution of Populations3h 53m

- 23. Speciation1h 37m

- 24. History of Life on Earth2h 6m

- 25. Phylogeny2h 31m

- 26. Prokaryotes4h 59m

- 27. Protists1h 12m

- 28. Plants1h 22m

- 29. Fungi36m

- 30. Overview of Animals34m

- 31. Invertebrates1h 2m

- 32. Vertebrates50m

- 33. Plant Anatomy1h 3m

- 34. Vascular Plant Transport1h 2m

- 35. Soil37m

- 36. Plant Reproduction47m

- 37. Plant Sensation and Response1h 9m

- 38. Animal Form and Function1h 19m

- 39. Digestive System1h 10m

- 40. Circulatory System1h 49m

- 41. Immune System1h 12m

- 42. Osmoregulation and Excretion50m

- 43. Endocrine System1h 4m

- 44. Animal Reproduction1h 2m

- 45. Nervous System1h 55m

- 46. Sensory Systems46m

- 47. Muscle Systems23m

- 48. Ecology3h 11m

- Introduction to Ecology20m

- Biogeography14m

- Earth's Climate Patterns50m

- Introduction to Terrestrial Biomes10m

- Terrestrial Biomes: Near Equator13m

- Terrestrial Biomes: Temperate Regions10m

- Terrestrial Biomes: Northern Regions15m

- Introduction to Aquatic Biomes27m

- Freshwater Aquatic Biomes14m

- Marine Aquatic Biomes13m

- 49. Animal Behavior28m

- 50. Population Ecology3h 41m

- Introduction to Population Ecology28m

- Population Sampling Methods23m

- Life History12m

- Population Demography17m

- Factors Limiting Population Growth14m

- Introduction to Population Growth Models22m

- Linear Population Growth6m

- Exponential Population Growth29m

- Logistic Population Growth32m

- r/K Selection10m

- The Human Population22m

- 51. Community Ecology2h 46m

- Introduction to Community Ecology2m

- Introduction to Community Interactions9m

- Community Interactions: Competition (-/-)38m

- Community Interactions: Exploitation (+/-)23m

- Community Interactions: Mutualism (+/+) & Commensalism (+/0)9m

- Community Structure35m

- Community Dynamics26m

- Geographic Impact on Communities21m

- 52. Ecosystems2h 36m

- 53. Conservation Biology24m

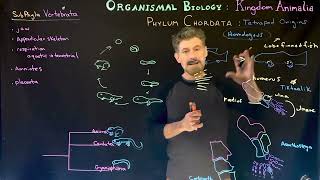

32. Vertebrates

Chordates

Struggling with General Biology?

Join thousands of students who trust us to help them ace their exams!Watch the first video

Bony Fish

Jason Amores Sumpter

Video duration:

5mPlay a video:

Related Videos

Related Practice